How does soap actually work?

Handwashing with soap is easy, inexpensive, and it saves lives. Seems like common sense, but how does handwashing with soap actually work? Why can’t you just use water? What even is soap?

To answer these questions, we’ll need to go back to school.

Bwacha and his friends are student ambassadors for handwashing. Schoolchildren are some of the most powerful advocates. See photos from Mukuyu Primary School in Mazabuka, Zambia. An ancient remedy

Bwacha and his friends are student ambassadors for handwashing. Schoolchildren are some of the most powerful advocates. See photos from Mukuyu Primary School in Mazabuka, Zambia. An ancient remedy

First, a history lesson. Humans have been using soap for a long, long time. The earliest recorded evidence of the production of soap dates back to around 2800 BC in ancient Babylon. Long before humans understood modern chemistry or biology, they noticed that certain materials, when mixed with water, did a much better job of cleaning than water alone.

At the most basic level, soap is a special type of salt derived from vegetable or animal fats or oils—for example, tallow (rendered beef fat), coconut oil, and olive oil are all popular soap bases. The oil or fat is combined with an alkaline metal solution, which breaks it down into the salt. Depending on additives, byproducts, and materials used, the final soap product can be solid, liquid, thick, thin, oily, or greasy. All types of soap do the same thing: remove dirt and the disease-causing germs it contains.

Removing dirt & germs, one micelle at a time

So, how does soap clean the dirt, grease, and oils off of your hands? To answer that, we’ll need a visit to chemistry class.

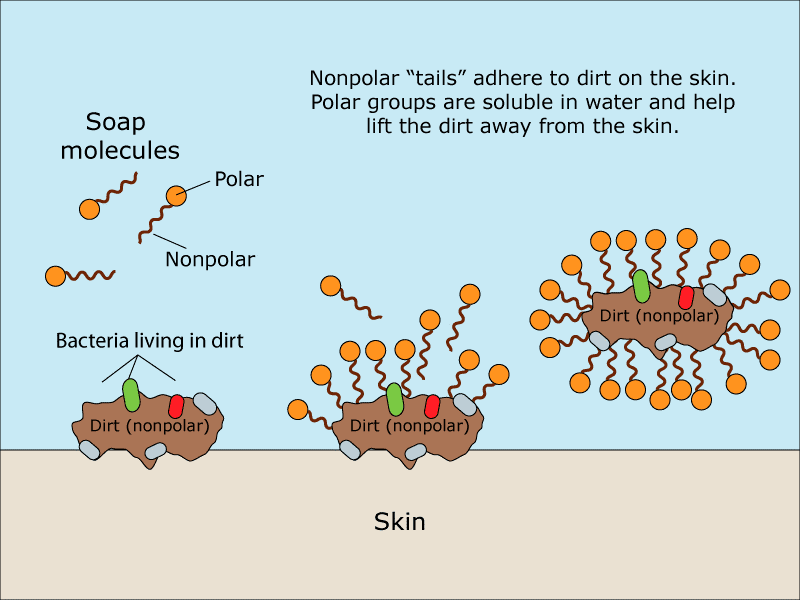

A simple mixture of sugar, salt, and water prevents deadly dehydration from diarrhea. The discovery of oral rehydration solution depended on the discovery of a sodium-glucose co-transport intestinal channel. Learn more about how ORS works to prevent death from diarrhea.You’ve heard the saying – oil and water do not mix. On a chemical level, that’s because the fatty molecules that make up oil, grease, and dirt are all non-polar molecules that don’t have a charge, while water molecules are polar. That’s why you get separate layers when you mix cooking oil with water or vinegar. This is important to understand for handwashing, because when disease-causing germs in fecal matter or dirt get on your hands after using the toilet or touching a contaminated surface, they mix with the natural oils on your skin and stay there. When you rinse your hands with water only, it’s ineffective against the germy oils that have lodged onto your skin. The water slips right off without mixing, just like it does with cooking oil.

A simple mixture of sugar, salt, and water prevents deadly dehydration from diarrhea. The discovery of oral rehydration solution depended on the discovery of a sodium-glucose co-transport intestinal channel. Learn more about how ORS works to prevent death from diarrhea.You’ve heard the saying – oil and water do not mix. On a chemical level, that’s because the fatty molecules that make up oil, grease, and dirt are all non-polar molecules that don’t have a charge, while water molecules are polar. That’s why you get separate layers when you mix cooking oil with water or vinegar. This is important to understand for handwashing, because when disease-causing germs in fecal matter or dirt get on your hands after using the toilet or touching a contaminated surface, they mix with the natural oils on your skin and stay there. When you rinse your hands with water only, it’s ineffective against the germy oils that have lodged onto your skin. The water slips right off without mixing, just like it does with cooking oil.

Meera is a community health worker in New Delhi, India. Watch her teach a group of new moms the why and how of handwashing.That’s where soap comes in. Because soap is salt derived from an oil or fat, it has a unique chemical structure that looks like a balloon. The balloon head is the salt—a charged, polar molecule—and it’s connected to a string or tail of non-polar fatty acids. The soap molecule can therefore act like a double-agent: the salty end is attracted to water, while the fatty tail is attracted to the dirt or oil. When you mix soap with dirt and water, the soap molecules break up the dirt and the bacteria it contains by forming circles around individual droplets—the fatty chains go in the middle facing the dirt, while the salt balloon tops form the outside of the circle facing the surrounding water. The wheel-like structure formed by the circle of soap molecules around the dirt or oil droplet is called a micelle.

Meera is a community health worker in New Delhi, India. Watch her teach a group of new moms the why and how of handwashing.That’s where soap comes in. Because soap is salt derived from an oil or fat, it has a unique chemical structure that looks like a balloon. The balloon head is the salt—a charged, polar molecule—and it’s connected to a string or tail of non-polar fatty acids. The soap molecule can therefore act like a double-agent: the salty end is attracted to water, while the fatty tail is attracted to the dirt or oil. When you mix soap with dirt and water, the soap molecules break up the dirt and the bacteria it contains by forming circles around individual droplets—the fatty chains go in the middle facing the dirt, while the salt balloon tops form the outside of the circle facing the surrounding water. The wheel-like structure formed by the circle of soap molecules around the dirt or oil droplet is called a micelle.

Soap molecules dislodge dirt, oil, and grease particles – and the disease-causing germs they carry – from your hands, one micelle at a time. [Source]When you wash your hands with soap, it dislodges the dirt, grease, oils, and disease-ridden fecal matter particles on your hands by creating these micelles. Surrounded by the soap, the oil molecules become suspended and distributed in the water rather than stubbornly clinging to your skin. This allows the dirt and germs on your skin—or on clothing, surfaces, or towels—to be rinsed away with the water. Ta-da!

Soap molecules dislodge dirt, oil, and grease particles – and the disease-causing germs they carry – from your hands, one micelle at a time. [Source]When you wash your hands with soap, it dislodges the dirt, grease, oils, and disease-ridden fecal matter particles on your hands by creating these micelles. Surrounded by the soap, the oil molecules become suspended and distributed in the water rather than stubbornly clinging to your skin. This allows the dirt and germs on your skin—or on clothing, surfaces, or towels—to be rinsed away with the water. Ta-da!

Today’s challenge

So now we know what’s happening on a molecular level, but what about the community level? Why does handwashing with soap matter so much for global health? And if soap has been around for so long, why are we still talking about it today?

For these questions, we need lessons from public health and the social sciences. The benefits of handwashing with soap are numerous. It significantly reduces the risk of diarrhea, typhoid, respiratory illnesses, and lots of other waterborne and infectious diseases. It is estimated that universal handwashing with soap could prevent 30% of all diarrhea cases. And because handwashing reduces illnesses and their long-term complications, handwashing also helps improve child growth, development, and school attendance around the world.

We know that handwashing, along with safe drinking water and toilets, save lives. But far too many people still lack access. Share our resources to join our call for equity: the universal health revoLOOtion.The problem is that, despite the low cost and ease of using soap, handwashing with soap is rarely practiced as often as it needs to be. Handwashing with soap requires water and soap to be available when and where people are relieving themselves, and 2.3 billion people worldwide still lack access to basic sanitation. Education and behavior change interventions are needed, too.

We know that handwashing, along with safe drinking water and toilets, save lives. But far too many people still lack access. Share our resources to join our call for equity: the universal health revoLOOtion.The problem is that, despite the low cost and ease of using soap, handwashing with soap is rarely practiced as often as it needs to be. Handwashing with soap requires water and soap to be available when and where people are relieving themselves, and 2.3 billion people worldwide still lack access to basic sanitation. Education and behavior change interventions are needed, too.

We can change this. Universal handwashing with soap is an essential part of the toolkit required to defeat diarrheal disease and help every child thrive. To reach this goal, governments, the private sector, civil society, and other stakeholders need to work together to promote handwashing with soap alongside clean water and sanitation.

We all need to give each other a hand – a clean hand, that is! Thankfully, soap is here to help make that happen.

Learn more from DefeatDD’s state of the field report, Stop the Cycle, a one-stop shop for diarrheal disease data available in English and French.

Learn more from DefeatDD’s state of the field report, Stop the Cycle, a one-stop shop for diarrheal disease data available in English and French.