Make handwashing a habit to prevent diarrhea… and grow taller, too

|

You might know that handwashing makes a huge impact when it comes to preventing diarrhea: if everyone made handwashing a habit, diarrhea risk would drop by nearly half! But did you know that good handwashing and hygiene habits can also help children reach their full growth and cognitive potential?

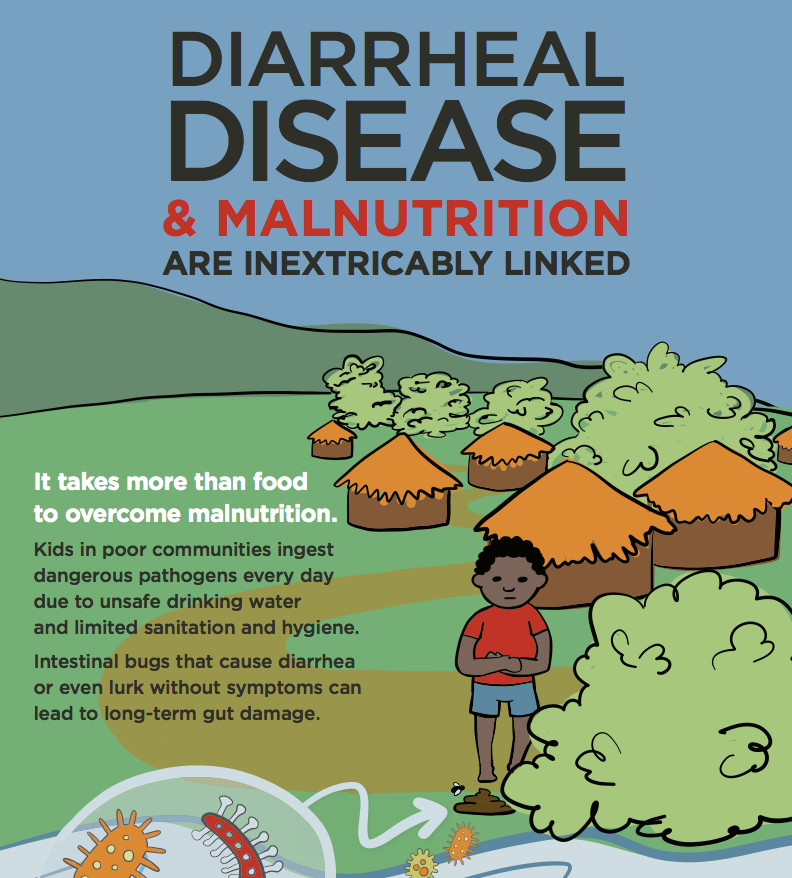

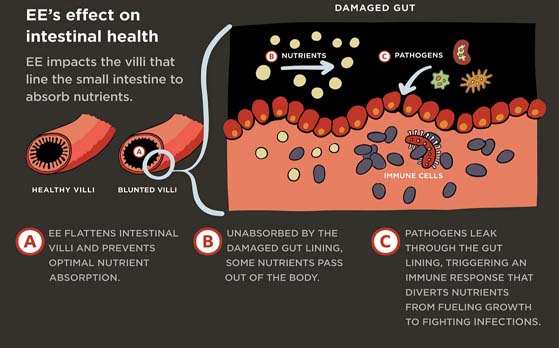

Long-term low-level gut damage, called environmental enteric dysfunction (EED), is an issue that brings WASH, nutrition, vaccine communities together to underscore the importance of a multifaceted approach to defeat the vicious cycle of malnutrition and diarrheal disease and help children grow healthy and strong.

We talked with EED expert and PATH research fellow Michael Arndt to shed some light on these seemingly unlikely connections.

First, tell us a little about yourself. How did you become interested in gut health?

When I came to the University of Washington in 2010, I worked with Dr. Judd Walson, who was running a clinical trial of empiric deworming to delay HIV disease progression in Kenyan adults. I learned a great deal about the immunological effects of soil-transmitted helminths from my master's thesis and was introduced to the concept of environmental enteric dysfunction (EED) while working on a project for the UW Department of Global Health Strategic Analysis, Research, & Training (START) Center. EED seemed to have such widespread impacts on child health, and there were many unanswered questions.

How would you define environmental enteric dysfunction (EED) in one sentence (or two)?

EED is a subclinical small-intestinal disorder characterized by mucosal inflammation, reduced barrier integrity, and nutrient malabsorption. “Environmental” is used in the name because this is an acquired syndrome, thought to be driven in part by multiple and repeated intestinal infections, with or without diarrhea, often experienced in settings lacking in adequate sanitation or clean water.

We usually hear EED and environmental enteropathy (EE) used in similar contexts. Is there a difference?

EED and environmental enteropathy are the same entity, having been called tropical enteropathy at one point as well. In 2013 a technical working group convened by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation recommended calling the syndrome EED in order to focus on the functional alterations occurring in the small intestine, which could be targeted by intervention approaches.

When you say that EED is “subclinical,” you mean that there are no overt symptoms. So why does it matter?

EED is important because it appears to be a major cause of stunting among children in low and middle income countries and has been associated with poor immune responses to oral immunizations, including rotavirus and polio vaccines. As stunting in early childhood is a marker of impaired immune protection and immune system development, sub-optimal cognitive development, and reduced economic potential, targeting EED in developing settings may yield multiple sustained population health benefits.

Environmental enteric dysfunction demonstrates why diarrheal disease and malnutrition can feed off of each other in a vicious cycle. Handwashing is a key interruption point for preventing the cycle. View the full infographic.

And is there currently an affordable treatment to address EED in low-income settings?

Unfortunately, there is currently no effective treatment for EED, though evidence from one clinical trial suggests that zinc or Albendazole (anthelminthic drug) may slow the progression of EED in children.

In the meantime, prevention can take us a long way. This year's Global Handwashing Day theme is "Make handwashing a habit." How can habitual handwashing and healthy hygiene behaviors help fight EED?

In conjunction with improved access to clean water and sanitation facilities, habitual handwashing and healthy hygiene behaviors have the potential to reduce the transmission of enteric pathogens to young children who are most susceptible to EED.

It's our WASH superhero, with the power to "flush the bad guys away!" Watch him team up with nutrition, vaccines, and ORS/zinc to save the village from the diabolical diarrhea villains.

Beyond clinical research, you also work with others to raise awareness about EED. Why is communicating about EED important to you?

It is important to communicate information about EED to organizations focused on delivering nutrition and vaccinations interventions because EED appears to be a major reason why in developing setting nutrition interventions often fail to reverse child stunting and oral vaccinations tend to be less efficacious. If successful interventions can be developed to treat or prevent EED, then we could unleash the unrealized potential of many existing health interventions to reduce child morbidity and mortality and improve cognitive outcomes.

What's the next frontier in your research on EED?

Non-invasive biomarkers for intestinal disruption/inflammation, microbial translocation, and systemic inflammation, many originally used to monitor inflammatory bowel diseases, have helped us understand more about how EED develops and may hold the key to a more nuanced and actionable understanding of the condition.

The Diarrhea Innovations Group (DIG), co-chaired by PATH and icddr,b, is convening a meeting ahead of this year's ASTMH Conference in Atlanta to discuss whether it is possible to productively distinguish “subtypes” of EED based upon the information provided by these different biomarkers. The goal is to identify the benefits and drawbacks for establishing a formal case definition, which recognizes separate but often overlapping EED pathologies with respect to disease risk stratification and development of interventions.

Photo credit: PATH/Gabe Bienczycki.