When diarrhea gets personal: One girl’s fight against rotavirus

|

Me in December 1991, just a few weeks before getting sick.

This post is part of the #ProtectingKids blog series. Read the whole series here.

There was once a healthy little girl who, just a few months before her second birthday, started to feel sick. Her tummy hurt, her forehead began to burn up, and then aggressive diarrhea and vomiting started. She became weak, pale, and severely dehydrated: although the girl was crying, her tears had stopped flowing. She was listless and limp, lying on the couch like a rag doll.

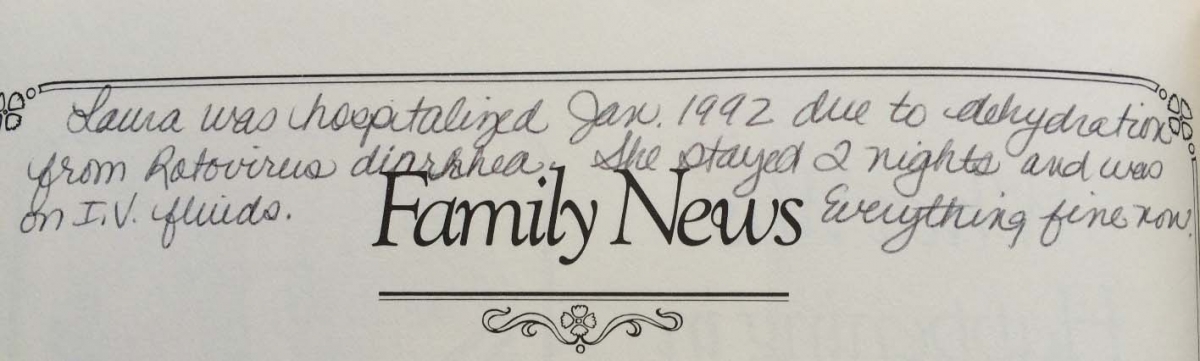

Her parents tried both juice and Pedialyte, a type of oral rehydration solution (ORS), but nothing would stay down. They were terrified. After 36 hours, they decided to bring her to the hospital. Doctors ran a few tests and determined that the diarrhea was due to rotavirus. Since there is no treatment for rotavirus other than rehydration, they gave her intravenous (IV) fluids—a feat for the nurse, given that the girl's dehydrated veins were so tiny.

That girl was me in January 1992. I only learned the full story recently. I had known I was hospitalized as a toddler, but I had no idea it was due to rotavirus, and I had never heard my parents' testimony of how horrible it was. This came as a surprise because, at the time I learned about it, I had been working at PATH for about a year on rotavirus vaccine advocacy and communications. I had been telling my parents about our newest projects when my dad remarked:

“We felt so helpless when you had rotavirus.”

“Wait… what?!” I said, stunned.

The rest of the story takes a more positive turn—my parents said I began to feel dramatically better after the first day in the hospital. My color brightened, my tears returned, and my fever dropped. On the second day, when it was time for my dad and sister to go home after a visit, I determined, "I go too!" and tried to rip my IV catheter out of my arm. “IV out!”

Much to my parents' relief, I only stayed in the hospital for two nights, returning home on the third day. I fully recovered thanks to the IV fluids.

My mom's entry in my baby book describing the incident.

After learning about this, there was first the mindboggling realization that the disease I had been researching and writing about every day had touched my family and me personally, and I had had no idea. Not only had rotavirus sent me to the hospital, it had also forced my mom to miss two days of work and cost my family a lot of stress and expenses.

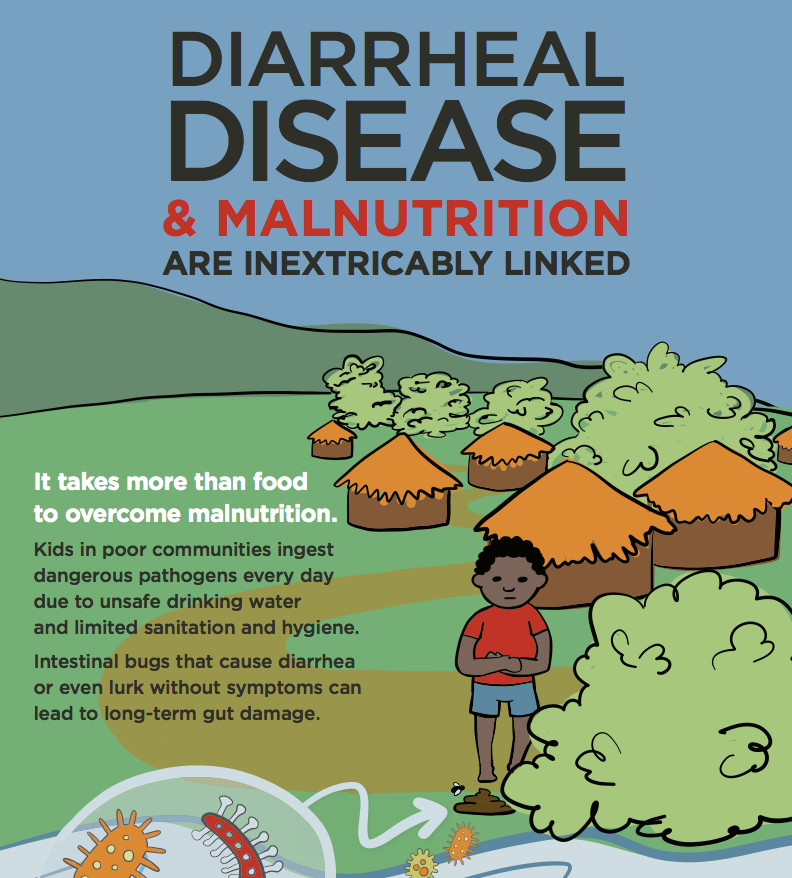

I then had the revelation that the little girl described above could be almost any little girl or boy, anywhere in the world, whether decades ago or today. Rotavirus is called the “democratic” virus—without protection from vaccines, rotavirus infects nearly all children everywhere, rich or poor, by the age of five and is the most common cause of severe diarrhea in the world. It does not matter if you are in the United States or Nepal, if you live in a mansion or a grass hut, or if you drink water from a river or a well: rotavirus is everywhere.

In many places in the world, however, a child in the same situation I was in may not be able to go to the hospital, or even if she is, the hospital may not have ORS or IV equipment. In those situations, diarrhea can become a death sentence. Rotavirus alone is estimated to cause hundreds of thousands of deaths—the vast majority in Africa and Asia—and millions of diarrhea-related hospitalizations in children under five each year. I am unimaginably lucky that my parents were able to get me the proper treatment. Without the IV fluids, they might have lost their little girl.

This is why rotavirus vaccines are so crucial. They are the best way to protect kids from rotavirus and the deadly, dehydrating diarrhea it can cause. First introduced in seven countries in 2006, rotavirus vaccines are now available in the national immunization programs of more than 75 countries worldwide, nearly half of which are lower-income countries supported by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Where children have access to them, rotavirus vaccines are saving lives, money, and a lot of parental grief.

Let's keep advocating until everyone, everywhere can be protected, because no parent should have to see his or her child suffer from a disease that is now vaccine-preventable.

My parents couldn't agree more.