Surviving Severe Malnutrition at icddr,b’s Dhaka Hospital

|

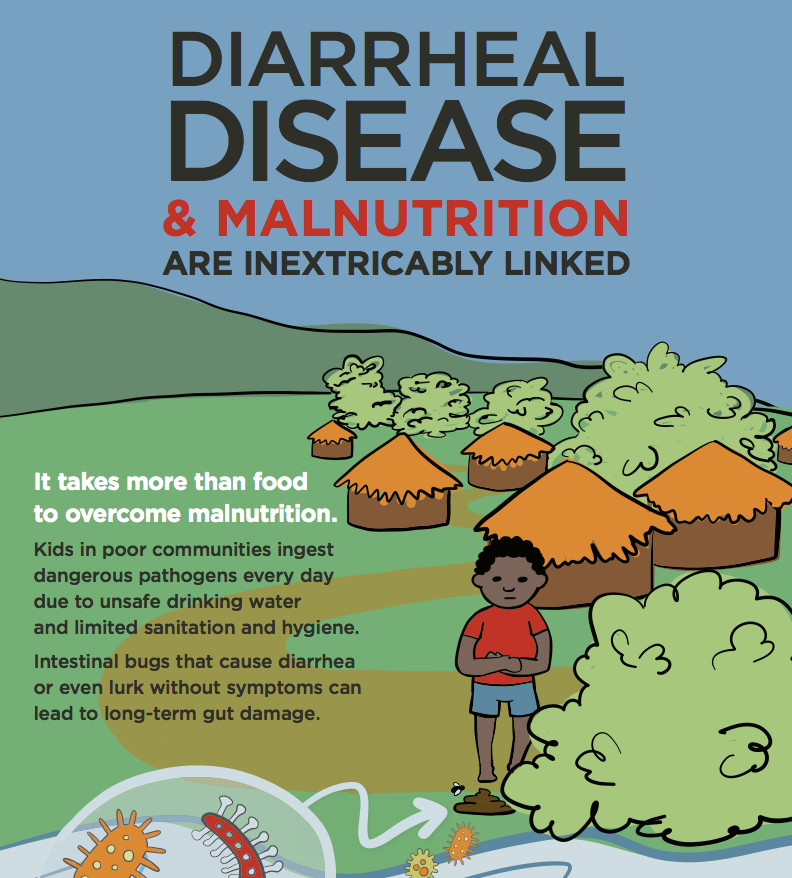

Every day, concerned families bring children of all ages to the famous Cholera Hospital run by the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b). The children are brought to be treated for diarrhoea, but many are suffering from other conditions, including severe acute malnutrition (SAM). Left untreated, SAM has a fatality rate of 30-50%. But researchers and clinicians at icddr,b have developed treatment protocols and interventions that dramatically improve childrens' chances of survival. My name is Yana and as an icddr,b staff member, I see this scene on a daily basis. I wanted to learn more about SAM and so I went into the Hospital to find out more.

Five and a half month old Alim arrives at Dhaka Hospital and within minutes is admitted by Nurse Khatun for recurring diarrhoea.

The busy hospital entrance is no easy scene to step into. At the triage counter, mothers and fathers comfort their crying children while nurses conduct preliminary assessments and register the children.

Nurse Majeda Khatun, who is on duty this day, tells me that the hospital admission process follows the World Health Organization (WHO) admission guidelines for malnutrition. These involve measuring and weighing children and checking for abnormal swelling in the feet for indicators of malnutrition. A child suspected of acute malnourishment is quickly referred to the hospital's ‘Short Stay Unit' for a more in-depth assessment.

The medical staff use a tablet to assess Sameha's (pictured) z- score (weight x height) where a z-score below -3 indicates SAM as outlined by the WHO growth standards.

As I am escorted through the Short Stay Unit, the doctors tell me that “before treating children with severe malnutrition, we must treat their acute diarrhoea and existing illnesses.” We walk over to eight-month-old Sameha, who was admitted a few hours earlier. At the hospital, doctors use a tablet computer with customised software to measure Sameha's z-score - a measure of growth - that confirms Sameha is suffering from malnutrition. One of an average 19 children per week that hospital staff diagnose with SAM, she is immediately put on a special liquid diet to increase her caloric intake, while having her diarrhoea treated with oral rehydration solution (ORS).

Azraful receives his zinc tablet from Dr. Mamun. Administration of micronutrients such as zinc in children with diarrhoea has proven to accelerate recovery and decrease chances of recurring diarrhoea in infants up to 5 years of age.

Next stop is the ‘Long Stay Unit', where I meet Dr. Mamun. He is about to give 26-month-old Ashraful his daily zinc tablet by mixing it with a few drops of water. Dr. Mamun explains that Ashraful has a 47% higher chance of surviving while in the care of the hospital and with treatment administered according to the hospital's SAM protocol, compared to non-standardised protocols. “Once the acute diarrhoea stops after a week of treatment of diet, antibiotics, slow rehydration, vitamins and minerals,” he says, “we will urge Ashraful's mother to take him to the ‘Nutrition and Rehabilitation Unit' to focus on treating his SAM.”

Saifun Nahar (left), a dedicated health worker at the NRU helps Hasan's mother, Hahina, with feeding.

Stepping into the Nutrition Rehabilitation Unit is completely different from visiting the previous wards. The smiling and playing children in this small, 10-bed ward were clearly no longer experiencing such discomfort or pain. Right away I was drawn to 10-month old Hasan, who was on his road to recovery from malnutrition. As part of his treatment, he was being fed halwa and kitchuri, local inexpensive food items that are rich in calories and easily prepared at home. Through intense feeding over a course of three-four weeks in the hospital, the health workers and Hasan's mother hope he will recover his lost weight and nutrients.

Hasan plays with a variety of toys as part of a scheduled psycho-social stimulation session at the Nutrition Rehabilitation Unit.

The effects of SAM can have implications well into a child's later years of development, as malnutrition can lead to growth stunting and delays in cognitive function . At the Dhaka Hospital, nutritional rehabilitation goes beyond feeding to incorporate psycho-social stimulation of the child. For an hour each day, Hasan gets to play with cognitive-focused games, as well as home-made toys, to increase his mental development and cognitive skills. I watch Hasan as he laughs and curiously grabs every toy in sight. His mother has a smile on her face and says that she is determined to see through his recovery.

Mothers at the Nutrition Rehabilitation Unit receive daily counselling from a health worker.

An hour of each day is dedicated to mothers, who get together for a counselling session with one of the hospital's health workers. A range of topics are covered, including food preparation, nutritional value of local produce, breastfeeding, and child development. In some cases, malnutrition in Bangladesh is not due simply to a lack of food, but due to lack of education or information as to how best to feed children. For many of these mothers, the sessions are the only source of reliable information when it comes to child care, and they are encouraged to share what they learn here with their family and friends when returning home.

Hasan smiling at the NRU ward after feeding and psycho-social stimulation.

Once Hasan achieves a 15% weight gain since admission, or his z-score improves to -2, he will be discharged from the Nutrition Rehabilitation Unit and his mother will be advised to come back for follow-up in a week. Follow-up sessions lasting up to a year are designed to prevent children from relapsing, monitor their ongoing well-being, and answer any questions the parents might have.

Thanks to the protocols developed through the organization's research, the fight against SAM at the Dhaka Hospital ensures that all children have the opportunity to recover from SAM and go on to lead healthy and happy lives.

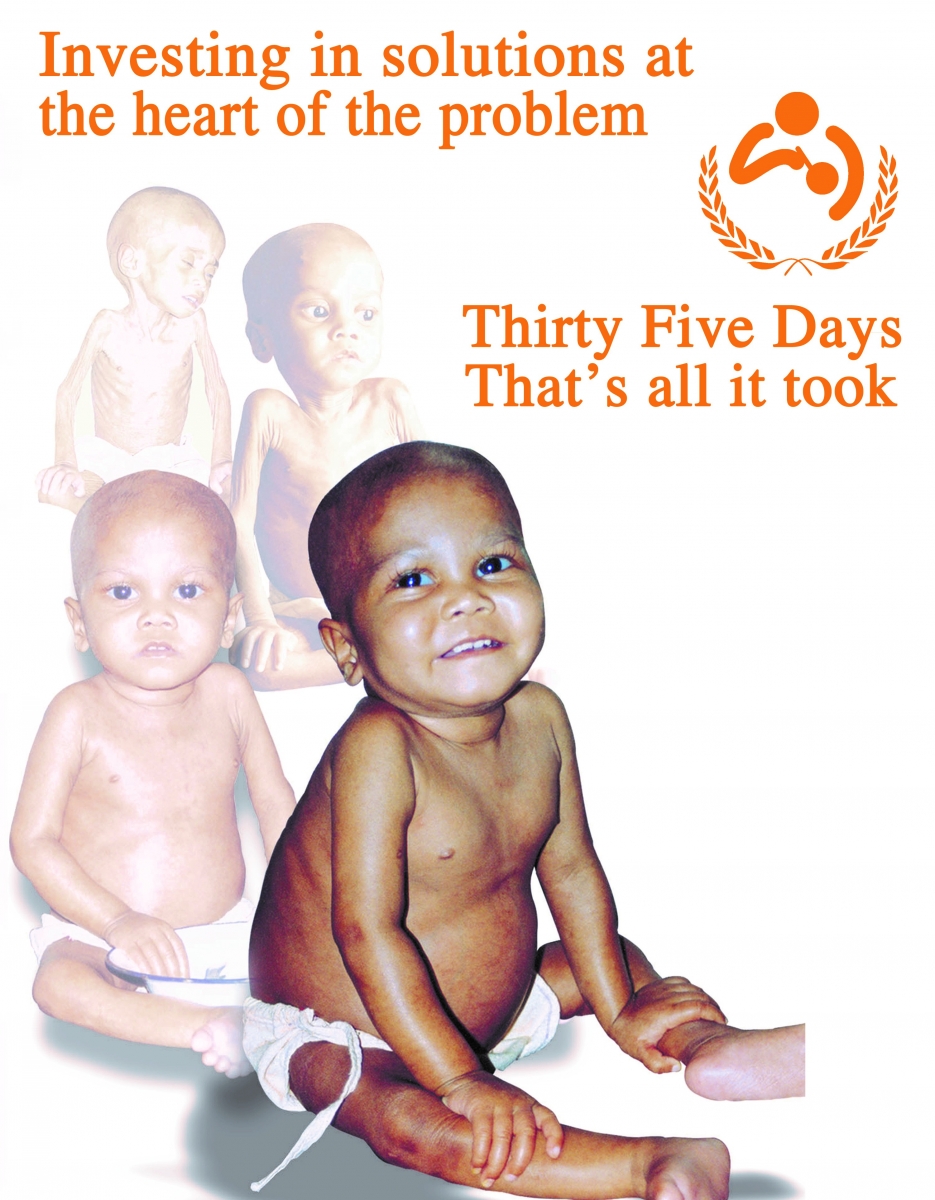

Sheema, is one of the hospital's most memorable children who had SAM. She was admitted in critical condition with diarrhea, malnutrition, and pneumonia, and her successful recovery after 35 days of treatment at icddr,b has been used as a case study since.