Social Franchising: Saving Lives and Treating Diarrhea in Rural India

|

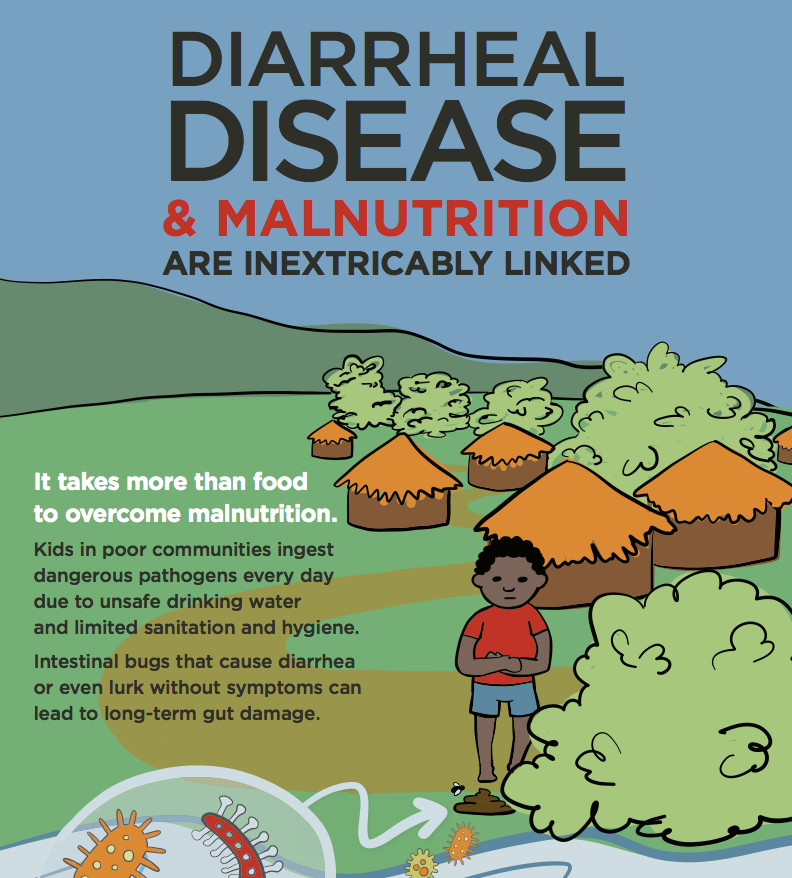

Diarrhea and pneumonia are the leading causes of mortality in children under 5, accounting for over 2 million deaths annually. More than 90% of these deaths occur in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where children in the poorest, most rural areas are disproportionally affected.

One of the largest barriers to treatment is lack of access to adequate healthcare. Poor quality of care, long distances to health centers, and lengthy wait times hinder use of government facilities. In the predominantly rural Indian state of Bihar, 93% of households reported not using government facilities at all. As a result, nearly two-thirds of households across India seek healthcare from private medical providers. In rural India this sector is largely comprised of unregulated and fragmented providers with little formal medical training. These providers are businessmen motivated by frequently conflicting aspirations: profit generation and service to their communities.

To overcome these challenges, World Health Partners (WHP) developed Sky - a rural franchise network that seeks to leverage these private providers' existing infrastructure and relationships to improve quality standards, while adding value to providers' businesses. In addition to connecting these providers via telemedicine to qualified doctors in cities, all franchise owners are trained in the treatment of basic diseases, given access to a large-scale supply chain of Sky-branded medications, and linked to higher levels of care through referral schemes. This model creates a value proposition allowing WHP to incentivize provision of less lucrative services and adherence to quality standards through the generation of multiple revenue streams for the providers.

To understand how WHP's model improves diarrheal care, consider the following scenario:

Pooja, a young mother of 4, brings her two-year-old son to the village doctor Malik—an informal provider who sells basic medicines in a small chemist stand—because her son has had loose stools for the past two days. Pooja stopped giving her son fluids because every time she feeds him, he has another episode of diarrhea. She asks the provider to give her some antibiotics to stop the diarrhea.

A common course of treatment that Malik and many other rural health providers in India might prescribe is an antibiotic for the infection and an anti-motility agent to slow bowel movements. For most informal private providers, medicine sales are a main source of revenue, with antibiotics providing much greater profit margins than ORS. In addition, the prevailing mentality—seen in developed and developing countries alike—is that antibiotics are the best quality treatment. As a result, if Malik doesn't give Pooja antibiotics, she may take the child to be treated elsewhere, affecting Malik's profits and reputation.

WHP aims to train private providers like Malik on the importance of appropriate treatment for diarrhea, which consists of oral rehydration salts (ORS) and zinc, rather than antibiotics, which can actually destroy “good” bacteria lining the intestines and worsen diarrhea. The commonly held belief of antibiotics as a cure all has contributed to the rise of antibiotic-resistant diseases in India.

Ideally, after training from WHP, Malik will have the skills and understanding to correctly counsel Pooja. In addition, Malik will receive a new supply of WHP's SkyMeds branded zinc tablets and ORS sachets through WHP's last mile-focused supply chain, which attempts to give him bigger profit margins than other brands and allows him to profit. With this strategy, zinc has the potential to replace antibiotics as the trusted “goli”, or tablet, for diarrhea.

While informal providers like Malik offer a unique inlet to improve the quality of care for India's poorest, most vulnerable populations, WHP still faces a number of challenges relating to the structure of this for-profit system and societal misconceptions of healthcare which continue to drive inappropriate use of antibiotics. WHP's goal is to address the above challenges through direct financial incentives, creating value-add propositions, and providing education by connecting them together in a cohesive, standards-driven support network. If successful, this approach could be a gateway to not only improve medical services for India's rural poor, but also to expand health education and awareness for both the informal providers and the communities they serve. Together, these improvements in understanding of health and quality of care have the potential to greatly reduce preventable deaths and the severe financial burden due to childhood illness across India's rural population.

-- Anoop Muniyappa is a 2nd year student in the UC Berkeley - UCSF Joint Medical Program. He is currently working with World Health Partners in India to evaluate the quality of care for childhood illness delivered by informal private providers within the WHP network.

-- Jacqueline Kingfield is World Health Partner's Development and Communications Project Manager.

Photo credit: PATH