Reading, Writing, and... Water Treatment

|

In remote villages of Western Kenya, children are asked to bring water to school.

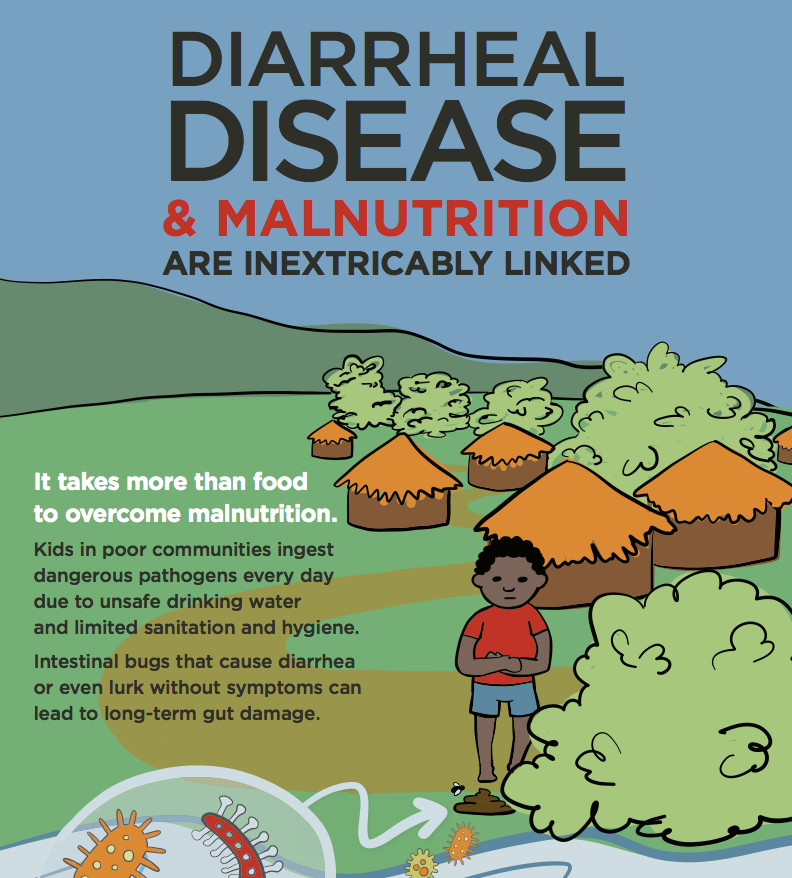

They collect water around the house or along their journey to school each day in a variety of worn containers of varying sizes. They collect surface water often turbid and filled with dirt, mud and possibly fecal matter that can cause diarrhea—often with terrible consequences. Before our safe water project started in their schools, the children would drink this water without any treatment. The ritual looked so harmless along the roads: adorable children with their school uniforms on, laughing and talking together along the dirt paths that lead to their schools, carrying their small containers of water.

We started the school-based safe water project in 2007 in 17 schools in Bondo District. We chose the schools based on their use of surface waters—water coming from a river, lake, or hole in the ground where rainwater has collected. This water is considered unprotected and often contains human and animal contaminants that can cause diarrheal diseases. None of the schools had access to a bore hole, protected spring, or other improved water source on their grounds.

We started the school-based safe water project in 2007 in 17 schools in Bondo District. We chose the schools based on their use of surface waters—water coming from a river, lake, or hole in the ground where rainwater has collected. This water is considered unprotected and often contains human and animal contaminants that can cause diarrheal diseases. None of the schools had access to a bore hole, protected spring, or other improved water source on their grounds.

We held a two-day workshop with two teachers and a headmaster in each of the 17 schools and taught them methods for treating water and proper handwashing techniques. We installed six (60-Liter) buckets with lids and spigots and gave each school a free three-month supply of PuR® and WaterGuard. PuR®, manufactured by the Procter and Gamble Company, is a flocculent-disinfection product that makes water that looks like mud turn completely clear . To the school children who started treating their water with PuR®, it looked like magic. Their faces lit up with joy as they watched the result happening right before their eyes.

The school strategically placed modified containers around the school grounds as stations for drinking water and handwashing. Children formed Safe Water Clubs and encouraged their classmates to learn about the importance of drinking treated water and proper handwashing.

The school strategically placed modified containers around the school grounds as stations for drinking water and handwashing. Children formed Safe Water Clubs and encouraged their classmates to learn about the importance of drinking treated water and proper handwashing.

We returned to the schools after three months, and again one year following the intervention. We found that in most of the schools, the safe water and hygiene project was still maintained. In a number of the children's households, their families had adopted water treatment behaviors, and absentee rates at school had dropped by 26 percent. Teachers told me that they truly believed their students were paying better attention and not having to run to the latrine, or miss classes because of diarrhea.

In one of our most active schools, the young girl who was the president of the safe water club was also named Elizabeth. It seems we share a passion for safe water, too.

-- Elizabeth Blanton is a Research Associate with PATH's Safe Water Program. She recently relocated to Seattle from Atlanta, Georgia, where she worked for eight years at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducting this research project and others. She is looking forward to hiking in the Pacific Northwest.