Policy change to address childhood pneumonia in Kenya

|

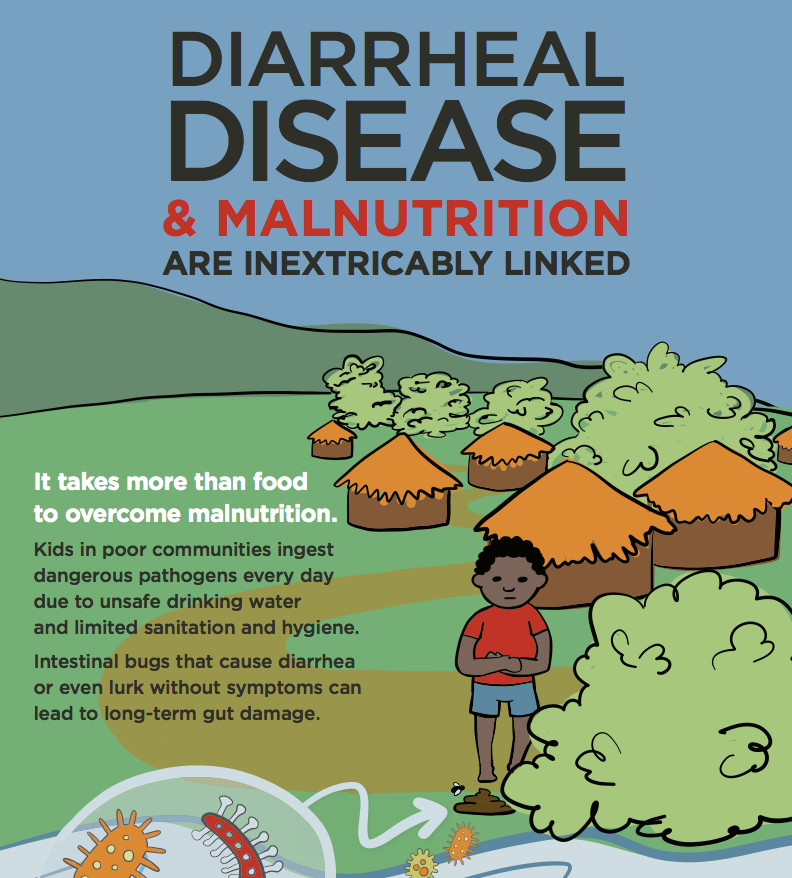

Pneumonia and diarrhea are the leading killer diseases of children globally. National policies that incorporate the latest global standards of care can help drive down these numbers. Kenya adopted an integrated national diarrheal disease policy in 2010, and today, PATH and partners are encouraging the country's adoption of global recommendations for pneumonia treatment.

I recently became an aunt to a boisterous little boy, well, that's if you count 2 years as recent! Since then, I've developed an even more personal interest in supporting work that focuses on preventable childhood diseases that continue to contribute to my country's less-than-ideal child mortality rates. One such disease is pneumonia. Globally, pneumonia kills more children below age five than any other disease and this statistic is largely mirrored in Kenya. Pneumonia accounts for roughly 16% of child mortalities in Kenya, or in other words, approximately 122,000 children under five each year.

Why is Kenya falling behind on its commitments to reducing child mortalities, and why does pneumonia remain a ‘silent killer' of children? Only half of children with suspected pneumonia receive the recommended antibiotic. This very simple statistic is symptomatic of the breakdown of the UNICEF/WHO framework which highlights 3 essential steps to reducing child mortality due to pneumonia. Basically, to better address pneumonia in children, the first step is to accurately recognize that a child is unwell with pneumonia; however, many caregivers cannot correctly identify the tell-tale signs of pneumonia (fast breathing and difficult breathing). Secondly, caregivers then have to immediately seek appropriate care from providers that can accurately diagnose and treat pneumonia. Finally, since the majority of pneumonia cases in Kenya are caused by bacteria, a full course of appropriate antibiotics should be provided as the recommended, affordable and effective treatment.

So how or where does policy change make a difference in how we address childhood pneumonia? To start off, by adopting the global recommendations on how pneumonia is classified and treated. WHO now recommends amoxicillin as first-line treatment; however, Kenya's treatment guidelines still reflect the old treatment regimen, which called for co-trimoxazole. While the country is currently scaling up integrated community case management (iCCM), which includes amoxicillin as first-line treatment, this is not reflected in the care provided by facility level health care providers.

PATH is currently working in partnership with the Kenya Pediatric Association (KPA) and UNICEF to advocate for this critical policy change that will align national treatment guidelines with current evidence and global recommendations. A critical component of this work is supporting the Ministry of Health in conducting a critical analysis of the global and local evidence that backs this change in treatment guidelines. But this is only a first step. Next we have to work on ensuring that the commodity is available in the country. This means having amoxicillin registered and included on the Essential Medicines List specifically for treatment of childhood pneumonia. And finally, work has to go into harmonizing treatment guidelines and training curricula for health providers to ensure standardized treatment within the country.

Kenya's recent step in introducing the pneumococcal vaccine is a step in the right direction, but as I have highlighted, more needs to be done. Implementing these important policy changes will institutionalize the simple actions we can take to save our children. So as I watch my nephew thrive and grow stronger and faster, I remain committed to ensuring that mothers and caregivers around the country can do the same with their little ones.

Photo credit: PATH.