The lag in rotavirus uptake in Asia: It’s all about perception

|

It all seemed that it would be easy back in 2006. The New England Journal of Medicine published landmark articles reporting the safety and efficacy of two new rotavirus vaccines in January of that year. And within weeks the US announced that it would recommend one of these vaccines for routine use in all US infants. Within months other countries in Latin America followed suit announcing inclusion of rotavirus vaccines into their National Immunisation Programmes (NIP). By 2007 there were over 25 countries that became “early-adopters” of rotavirus vaccines. But then progress appeared to slow rather than accelerate.

The ground work had appeared to have been well laid to help public health policy-makers in all other countries to quickly follow with similar recommendations to rapidly introduce rotavirus vaccines. “Proof of local disease burden” and “evidence of cost-effectiveness” were identified as key information that would drive policy decisions on vaccine introduction. From the late 1990s, the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) facilitated the establishment of regional Rotavirus Surveillance Networks to collect this all important disease burden data. The Asian Rotavirus Surveillance Network was the first to be formed in February 1999. A range of high-, middle- and low-income countries in the Asian region started to collect information on how many children were admitted to hospital with diarrhoea and the proportion of these admissions that were due to rotavirus. A WHO generic protocol to collect these data was simple to follow and required that participants only needed to select a small number of sentinel surveillance hospitals.

As more and more data emerged showing the rotavirus virus was the dominant pathogen causing admission for diarrhoea in children under-five years of age, it seemed more and more likely that decision-makers would enthusiastically embrace these new vaccines. The WHO made a recommendation in 2007 that rotavirus vaccines should be considered for inclusion in the NIPs of countries were efficacy had been demonstrated. This essentially meant the Americas and Europe, as these were the sites of the initial efficacy studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine. However by 2009 data became available from studies done in Asia and Africa and the WHO updated its recommendation to advise that rotavirus vaccines should be included in ALL NIPs, and for those countries with high mortality from gastroenteritis in children under five years old, the WHO emphasised that the vaccines were STRONGLY recommended.

Yet despite this unequivocal recommendation, the response from many Health Ministers, vaccine advisory committees, and public health officials has been somewhat underwhelming. There was no clamouring to obtain the rotavirus vaccines following the announcement of the WHO recommendation. Yet 2009 was the same year that many Health Ministers were rushing to buy stockpiles of pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine - at a stage in many countries when it was already obvious that the likely impact of this virus on mortality would be no greater than that of normal seasonal influenza. Why the urgent high-level meetings to discuss influenza vaccine but not similar meeting to discuss how to expedite introduction of these important new rotavirus vaccines?

Some “early-adopter” countries (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, El Salvador, Mexico, Panama, and the US) have witnessed approximately 70% fewer hospital admissions due to rotavirus illness and approximately 35% fewer hospital admissions due to diarrhoea of any cause during the first two years of life. In high- and middle-income countries gastroenteritis can account for around 15% of all general paediatric admissions in children under five years old. If we could reduce these admissions by 35%, it means that overall there will be 5% less paediatric admissions every year. This is a massive effect. Think of the impact on the front-line medical and nursing staff. Think of the impact on hospital beds. Think of the reduced risk of nosocomial infection. Hospital Administrators should be jumping up and down demanding that rotavirus vaccines be introduced as quickly as possible. Sadly they don't yet seem too excited about this potential intervention that could boost their limited resources.

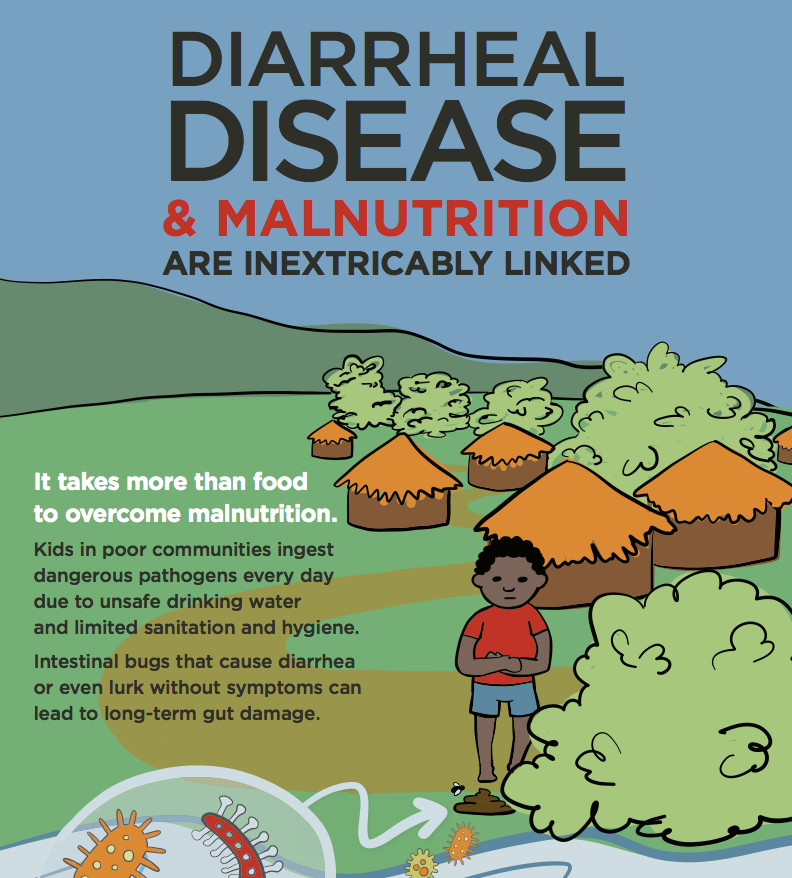

In 2008, there were an estimated 453,000 deaths from rotavirus in children under-five years, making it one of the leading causes of death in this age group. In Asia in the same year there were an estimated 188,000 deaths from rotavirus. This is equivalent to about 500 child deaths every day. Nearly 95% of these deaths occur in the low-income developing countries where access and availability to health care is limited. Even if the Health Ministers of these poorer developing countries do not have the resources to immediately include rotavirus vaccines in their NIPs, one would at anticipate (naively) that rotavirus vaccine introduction should be high on the Agenda of every G8 meeting - ahead of the GFC (global financial crisis) and similar mundane topics.

2.4 million child deaths could be prevented by 2030 by accelerating the introduction of rotavirus vaccines. To achieve this goal GAVI and its partners plan to support the introduction of rotavirus vaccines in at least 40 of the world's poorest countries by 2015, immunising more than 50 million children. GAVI initially gave support for rotavirus vaccines in 2006 and since then, introductions have occurred in Nicaragua (2006), Bolivia (2008), Honduras (2009), Guyana (2010), Sudan (2011), Ghana (2012), Rwanda (2012), Moldova (2012) and Yemen (2012).

As of August 2012, 41 countries have introduced rotavirus vaccines into their NIP. Although many countries in Latin America started using rotavirus vaccines in their NIPs more than 5 years ago, no country in Asia had done so until the Philippines announced in January 2012 that it planned to vaccinate an estimated 700,000 children annually from the poorest communities. Thailand is the second country in Asia to announce the partial introduction of rotavirus vaccine into it's NIP (Sukhothai Province). Currently no GAVI-eligible Asian country has introduced rotavirus vaccine.

Clearly Asia needs to do more and try harder - and to do this quickly. It has lost the opportunity to be an “early adopter” region - let's hope that Asia won't be known as the “last-adopter” region.