International Women’s Day: Empowering Women to Transform Lives as Social Entrepreneurs

|

Adolescent girls in Maharashtra, India.

Lorelei Goodyear is a senior program officer at PATH and a committed advocate for women's health. Her work on PATH's Healthy Households Initiative empowers women through entrepreneurship that enables their communities to live healthier lives. Lorelei, and the women reached through this project, truly know how to #MakeItHappen.

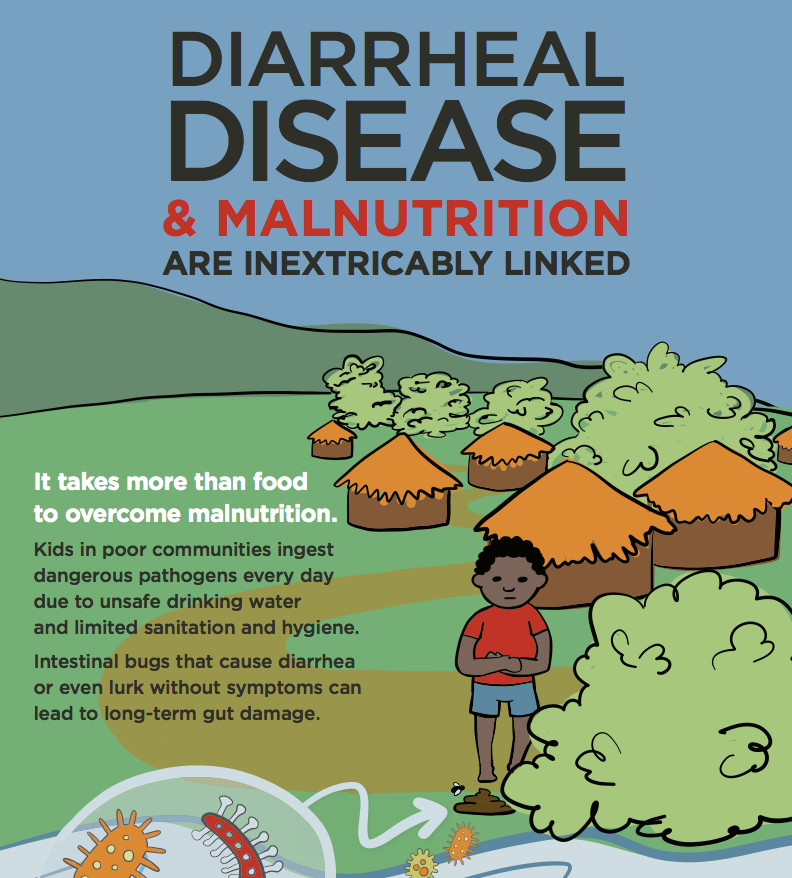

My whole career has focused on increasing options for women and girls so that they can achieve their full potential. I have focused primarily on reproductive health because deciding if and when to become a mother is such a pivotal point in a woman's life. Eight years ago I became a mother and took on a new role leading PATH's research and evaluation on safe water technologies. I quickly learned that diarrhea caused by unsafe water is a leading killer of children and safe water plays a crucial role in maternal and child health.

There are many effective water treatment methods, but getting people to use them is a big challenge. After experimenting with a variety market models, we had the best results (highest rates of adoption) by training local entrepreneurs to sell water filters in their communities and providing consumer loans that made filters affordable through small payments over time. In nine months, we tripled the use of water filters in a community in Cambodia. We tested the same approach with latrines, and Cambodian customers were four times more likely to buy them when offered a loan.

For our Healthy Household Initiative (HHI), we built on this success and added clean cookstoves and solarlights (to reduce indoor air pollution that contributes to respiratory illnesses). By selling a product bundle, homes would become healthier and social entrepreneurs would have an incentive (profits) to sustain and scale up without relying on donor support.

Early this year, I traveled to Maharashtra, India, to review the results of our first HHI test run. The trip had a profound effect on my understanding of the power of this approach to not only reduce childhood illnesses, but also radically improve the lives of women and girls.

In Maharashtra we brokered a new relationship between Sakhi Unique Rural Enterprise (SURE) and their sister organization Sakhi Samudaya Kosh (SSK). SURE trains women to sell an array of health products. These entrepreneurs are called Sakhis, or “friend” in the local language. SSK makes loans for income generation, but had never offered consumer financing for products sold by Sakhis. The HHI pilot was also the first time Sakhis had ever tried to sell latrines.

Varsha shows the HHI sales flipbook to women in her village.

I met Varsha at a gathering of Sakhis. She wore a bright red sari and spoke in a soft voice. I recognized her as one of the more shy Sakhis I had met 7 months earlier. She said that initially she had serious doubts about trying to sell a bundle of products, especially the latrine, which cost much more than any of her other products (US $200) and was embarrassing to talk about.

Her husband supported her joining the project, even though it took time away from her being at home and working as a tailor. But her in-laws complained that the HHI training took her away from home and she had nothing to show for it. Her field supervisor encouraged the family to be patient.

After Varsha started earning a ten percent margin on the sale of latrines, filters, stoves, and lamps she became bolder. She even described to me a sales pitch that she presented at a community gathering of 1500 people. As she spoke, her voice became stronger. She started laughing at her own story and positively beamed. After six months, Varsha had earned $630, which is six times what a Sakhi normally earns.

Varsha receives an award from Lorelei and a local official for being a top selling Sakhi of HHI products.

I also met Uma, one of Varsha's customers. Over seventy percent of families in Uma's village do not own a latrine, so they have to defecate in the open. Uma had long wanted a latrine, but her husband wasn't interested. She would get up before dawn to do her business under the cover of darkness. She used to go to the field near her house, but farmers chased her away. So she and her daughters squatted along the main dirt road that ran through their village. It was embarrassing when men would come by, but the women wear saris so can just stand up and not be exposed. It is harder for girls, who have to quickly get their pants up.

Uma's daughter Gita recently started her period. Uma noticed that Gita intentionally ate and drank less during her period to minimize how often she would have to relieve herself. By going less, she tried to avoid the shame she felt because all she had were rags to catch her blood and nowhere to change or clean them.

This renewed Uma's argument that it was time to get a latrine, and her husband finally gave in when he learned she could get a loan. Today, having a latrine makes her feel safer, and she asked if, in the future, we could also offer loans for girls' higher education, because she wants Gita to go to college.

Varsha and Uma taught me that having access to healthy household products and loans is transformative. So much so that we are now seeking funding to expand the model to include an explicit focus on gender equity and women's economic empowerment.

The government of Maharashtra has asked our partners at SURE and SSK to scale up HHI to reach 90,000 households. PATH played a catalytic role in helping launch HHI, but it is our partners and the Sakhi entrepreneurs who are well on their way to taking it to scale.

Photo credits: PATH.