Government spending priorities – where should nutrition rate?

|

[Dad joke alert] “Yesterday, I swallowed some scrabble tiles by mistake. The next time I go to the toilet, it could spell disaster”. Bit of a stupid joke, I apologise, but the dubious function it performs in this blog is to show how what you put into your mouth is an important factor in what comes out the other end. This might sound a little obvious, but a healthy diet is a key determinant in the health of your gut and consequently whether or not you suffer from diarrhoea.

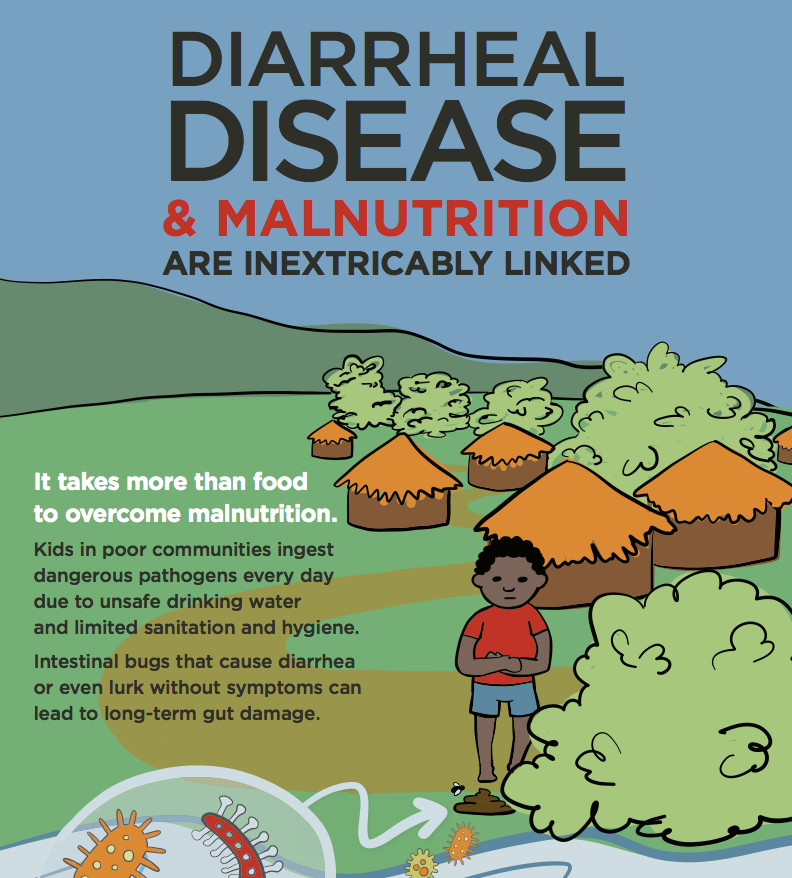

A child who is undernourished is at a higher risk of suffering from diarrhoeal disease - and diarrhoeal disease kills more children than AIDS, malaria, and measles combined. Undernourished children are at risk of suffering from diarrhoea because the lack of nutritious food doesn't give the gut what it needs, and because the lack of nutritious food damages their immune system's ability to fight off infections. To complete the picture, when children are suffering from diarrhoeal disease they are less able to absorb nutrients into their body. So diarrhoea is both a symptom and a cause of under-nutrition.

I recently went to visit Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), to talk to a range of people about what is being done to tackle the incredibly high level of child under-nutrition there. Currently, 43%, or about 5.5 million children, under the age of five are chronically undernourished. As part of a research project we are asking about how governments in fragile and conflict-affected states are combating the under-nutrition crises in their countries.

In countries suffering from persistent conflict and instability, nutrition is not always seen as a governmental priority. Government departments like health and agriculture which could, with sufficient budget and focus, make a real difference on child malnutrition just do not have the wherewithal to make it happen.

A refreshingly honest, if depressing, reason for this lack of government urgency was given to us by a Member of Parliament: they had decided to prioritise the defence budget; they want to deal with the conflict in the east of the country before they had the space to deal with human development issues like health and nutrition.

The conflict in the Kivus in the east of the country is forcing people to flee from some of the most fertile land. This means that cultivation and harvest is disrupted, significantly depressing yields and leading to scarcity and higher prices. In turn, lack of access to fertile land and therefore food exacerbates the conflict. However, conflict is largely restricted to the east, with the majority of the country relatively peaceful. Even in these non-conflict contexts, agricultural investment is low and undernutrition extremely high; these areas are largely forgotten, especially by the development community.

This leads to a really key question: should undernourished children be a higher or lower priority than dealing with an ongoing conflict in a restricted area of the country? We in the development community have isolated ourselves from difficult questions like this - our role is to care about the undernourished child. But the government of a country dealing with a long-term and protracted conflict feels like it has to make these difficult choices.

During the last resettlement programme for combatants in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo, there was an attempt to help demobilised soldiers to settle on land as farmers; however it was not well managed, and ex-soldiers found themselves with no land and nothing to do - many of them simply went back to fighting and the conflict became worse. This was a lost opportunity, both for the conflict and for nutrition.

The government of the DRC with the help of the international community really must find a way of prioritising childhood undernutrition; not just to deal with the injustice but for pragmatic reasons as well. Without dealing with the underlying causes of the conflict, they will never see a lasting peace; those underlying causes include lack of access to food and the land to grow it on. Furthermore, good nutrition is central to the development of a healthy workforce, necessary to help a country grow its economy.

For instance, it has been shown that poor nutrition can make people 10% less productive, and it is estimated that Bangladesh has lost over $1 billion because of undernutrition.

The Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo is rightly concerned about the conflict in the east, but it simply cannot tackle the conflict while ignoring the nutrition crisis. The two problems are linked and neither will be solved through simply investing in the army.