The DHAKA score: a new paradigm for diarrhoeal disease treatment

|

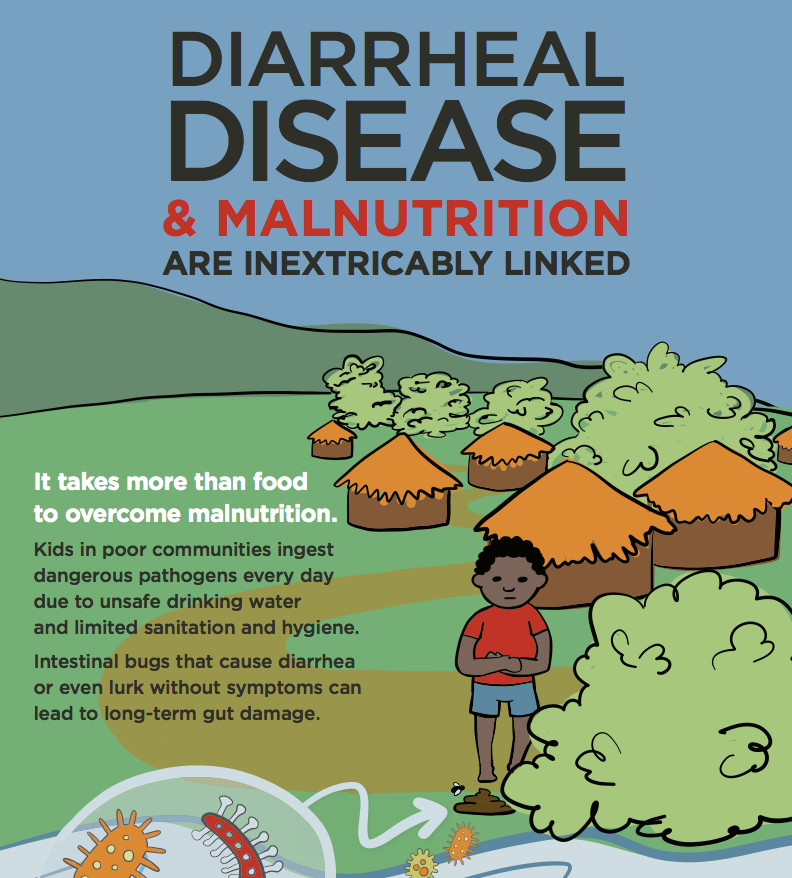

While healthy adults can often recover easily from common diarrhoeal pathogens, they have a devastating impact on children: according to the World Health Organization (WHO), half a million children die every year due to diarrhoea, with the majority of deaths occurring in poor countries across the Global South.

Most of these children die because their bodies lose too much water through diarrhoea. The treatment of diarrhoeal diseases like cholera or rotavirus is, therefore, focused heavily on the treatment of dehydration.

In advanced economies, treating dehydration is neither technically nor logistically challenging; most children infected with diarrhoeal pathogens have access to high quality medical care. Resource limitations do not constrain the availability of hospital beds or IV drips. However, in situations of scarcity, the treatment of dehydration becomes much more complicated.

Oral rehydration solution (ORS) was revolutionary because it offered a cost-effective alternative (a simple solution of salt and sugar) to IV fluids and greatly expanded the number of children who could be treated for dehydration in resource-poor settings. But the most severe cases of dehydration can only be effectively treated with IV fluids, which is more expensive than ORS and requires skilled medical staff.

In resource-limited conditions, effective public health can only be achieved through efficient allocation of scarce medical services. In the context of diarrhoeal disease, this means that it is very important to accurately determine the severity of dehydration in infected children to avoid wasting expensive IV fluids when children can instead be treated with ORS.

An easy-to-use and accurate clinical test for dehydration severity will (1) help avoid wasting expensive IV fluids when they are unnecessary and (2) save lives by catalyzing the use of ORS treatment to eliminate preventable deaths from diarrhoea in the resource-limited settings where they are most likely to occur.

Quantifying dehydration

The current “gold standard” test for measuring the severity of dehydration relies on measuring post-illness weight gain after recovery (even though this measure has issues, it is inherently more objective than clinical diagnoses based on external symptoms). However, this gold standard can only assess the severity of dehydration after the patient has recovered. Currently available diagnostic algorithms are either vulnerable to inaccuracies or too resource-intensive to be used in poor countries.

To address the pressing need for accurate, affordable and easy-to-use clinical measures of dehydration, researchers at the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), alongside collaborators from Brown University, developed an improved clinical score for dehydration assessment called the Dehydration: Assessing Kids Accurately (DHAKA) score. Through a study recently published in Lancet Global Health, the team compared the accuracy of the DHAKA score to the currently available methods in 496 children in Bangladesh and found that the DHAKA score is significantly more accurate and reliable.

Combining local contexts with global science

The DHAKA score was developed by researchers who could combine evidence-based science with a nuanced understanding of the challenges of providing healthcare in resource-limited settings. And the people most capable of empirically understanding the problems of the Global South are researchers living and working there.

Without donor support and the institutional resources of research centres like icddr,b, projects like the DHAKA score may never have been attempted. As global development programs are faced with increasing budget cuts, the story of the DHAKA score should serve as a reminder of the continued importance of supporting scientific research in the Global South.