The (breast)milk of human kindness

|

A proud new mother in India cradles her newborn. Photo credit: Richard Franco.

Baby Whitney arrived fourteen weeks early in 1980. Her mother Lisa Kidd traded visions of first snuggles in a newly minted home nursery to long days and nights at the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of Portsmouth Naval Hospital in Virginia. More than two hundred miles from home, what the hospital lacked in convenient location it made up for with the region's leading technology and expertise. Far from their families, Lisa and the other NICU moms supported one another through some of their most harrowing days. But round-the-clock vigilance was not feasible for everyone, and when many mothers had to leave for trips home or others could not even afford travel to the hospital, Lisa extended support to her new community - she donated her excess breast milk. (Full disclosure: Lisa is not only a generous and fantastic mother; I can directly attest that she is a great mother-in-law too).

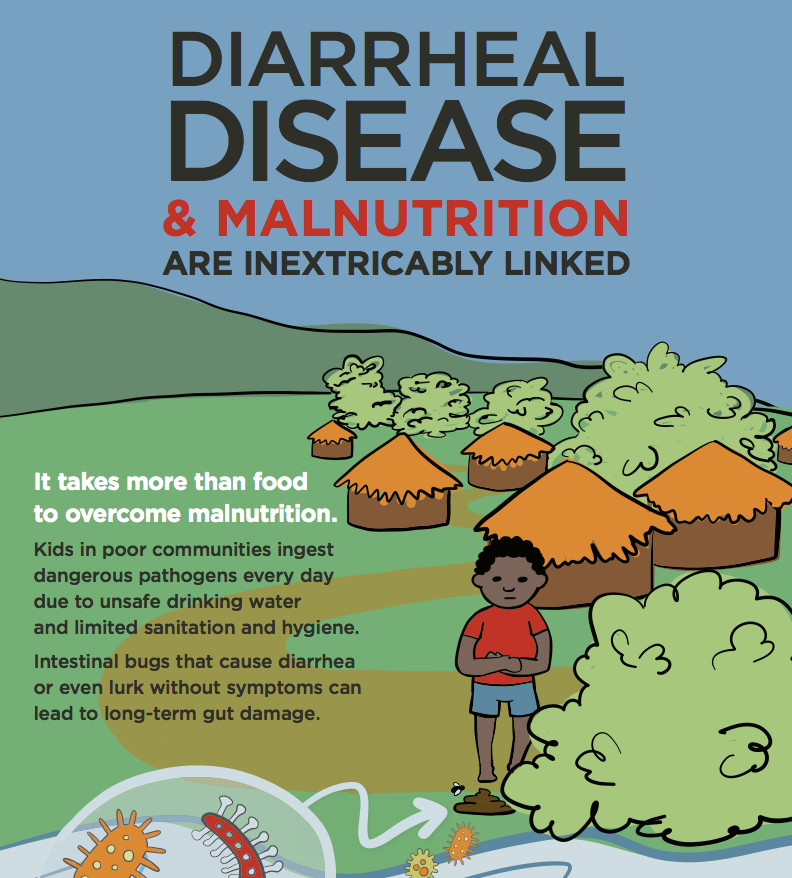

Human milk is the single most powerful intervention to save babies' lives, providing the unique nutrition and immune support they need to survive and thrive. Compared with formula, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics, breast milk reduces the risk of sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates, reduces the time hospitalized infants remain in care, and reduces feeding intolerance, diarrhea, gastric issues, and other dangers. But while breastfeeding may seem like a simple, straightforward—not to mention rigorously scientifically proven—intervention, neonatologists worldwide report that between 15 to 40% of infants in NICUs do not have access to their mothers' milk.

The World Health Organization recommends the safe use of donor milkfor vulnerable babies who cannot be fed their mother's own milk. When a mother has died or has a health issue that makes breastfeeding impossible for either short- or long-term, donor breast milk is a safe and effective alternative. Facilities pasteurize donated milk to ensure it is safe, and then freeze it until needed. However, scaling up this lifesaving intervention has been challenging in poor countries.

Hospitals in low-resource settings face technological barriers to safe milk banking (more on that later), and challenges persist among communities in the general population, as well. Inappropriate, aggressive marketing of breast milk substitutes like infant formula can undermine parents' confidence in breast milk and distort perceptions. Lack of awareness is a crucial contributor to the alarmingly low rate of exclusive breastfeeding (37%) in low- and middle-income countries. In fact, the WHO International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes calls on countries to protect breastfeeding and enact laws against the inappropriate marketing of breast-milk substitutes, feeding bottles, and teats. When breast milk substitutes are necessary, the code aims to ensure they are used safely. A new report provides an update on country-specific progress to enforce laws on marketing breast milk substitutes.

Appropriate infant and young child feeding, including breastfeeding, is so essential that efforts must extend beyond a single intervention to promote a shared understanding of its value and make the case for sustained investment. Through our Mother and Baby Friendly Initiative Plus, PATH applies a comprehensive model for improving infant and young child feeding practices, including increased access to donor breast milk for at-risk mothers through human milk banking. Our projects in South Africa, India, Kenya, and Vietnam focus on developing locally adapted, government-led, quality systems for ensuring safe access to human milk for all infants. We are also working on innovative and cost-saving technologies for low-income settings, like our mobile-phone app that directs and monitors a simple flash-heat pasteurization process and a rapid, point-of-care diagnostic device for screening donations. On the flip side, for a smaller group of infants who have difficulty breastfeeding, such as those with cleft-palate or who are born pre-term, we are partnering to accelerate access to the NIFTY cup, which features unique reservoir and flow channels that allow infants to lap or sip at their own pace. This comprehensive approach also prioritizes caregiver counseling on infant and young child feeding practices and kangaroo care (skin-to-skin contact). Counseling emphasizes WHO recommendations for exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months, addresses problems with breastfeeding including insufficient breast milk, and highlights complementary breastfeeding through two years of life.

In Kenya, we are documenting improvements on exclusive breastfeeding rates through the Baby Friendly Community Initiative, funded through the USAID Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP) and conducted in partnership with the Ministry of Health and UNICEF. Success at the community level is informing the development of an implementation package to guide scale-up. Through MCSP, PATH is also working to revitalize the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative in Malawi in partnership with Ministry of Health, partner organizations, and WHO. But these interventions can only be taken as far as government commitments, resources, and funding allow. That's why PATH is helping to promote supportive policies that enable countries to set aside targeted resources for comprehensive breastfeeding strategies.

Evidence is overwhelming for the pivotal benefits of a mother's milk, and when a mother is unable to provide her own, ensuring access to safe donor milk helps keep this promise of a healthy start to vulnerable infants. This network of care—built on the generosity of mothers like Lisa and her peers around the world—can save lives simply and safely. But it is only as strong as the comprehensive programs and policies that sustain it.