Modeling the long-term impacts of enteric infections

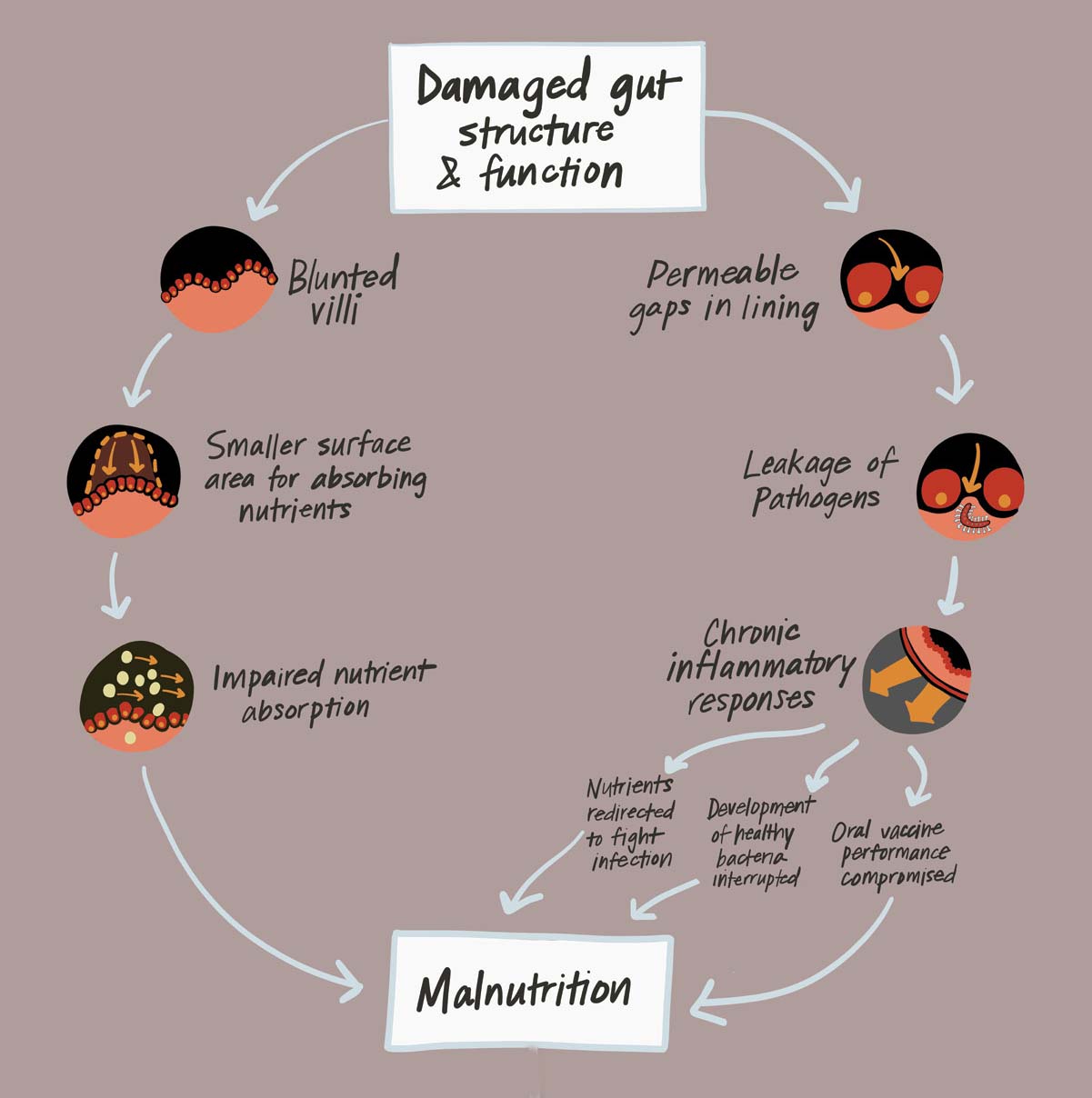

Our graphic on gut damage illuminates a few of the ways enteric infections exacerbate malnutrition. Researchers like Dr. Richard Guerrant are continuing to uncover new insights about how these pathogens cause long-term damage.

Diarrheal disease is a crisis for the preventable child deaths it causes, and yet that’s just part of the story. An underappreciated consequence of repeated enteric infections is that it can have crippling, lifelong impacts in children.

We spoke with Dr. Richard Guerrant, lead author of a recently published paper on laboratory modeling of enteric infections, which sheds light on how these infections cause damage. This knowledge can help improve existing tools and create new ones.

Can you explain the “triple burden” of common early childhood enteric infections, and how this research contributes to our understanding of it?

Careful field studies in Asia, Africa, and Latin America over the years have shown that the vast majority of viral, bacterial, and parasitic infections occur over the first 2-3 critically formative years of life without causing diarrhea. However, these “silent” infections are often associated with intestinal inflammation or other metabolic effects that can cause long-term problems:

- Stunting (declined height-for-age ratios over the critical first two years of life)

- Cognitive impairment (often best assessed through measuring higher executive function by 7-9 years of age)

- Metabolic syndrome later in life, a risk factor for early morbidities and mortality

The laboratory models we studied of these infections complement the field studies and can help us better understand which pathogens are responsible for which aspects of this triple burden, opening the door for us to intervene.

What did you learn from the laboratory models about how and why enteric infections stunt growth?

Complementing field studies noted above in children, the laboratory models show that many of the same pathogens (like Shigella or Campylobacter) often cause inflammation via pathways that prevent the production of key growth factors from the liver. This inflammation, or other mechanisms, can damage the gut’s absorptive function of key nutrients or trigger potentially damaging immune responses to normal growth and development.

What can this research suggest about potential interventions (either novel and/or better targeting of existing tools)?

Understanding key pathogens, their effects, and potential mechanistic pathways arm us with the knowledge we need to reduce deleterious, potentially long-lasting impacts. These pathways of damage in the body can serve as targets for new drugs or vaccines.

Alternatively, interventions that target ways that the body repairs damage or helps restore normal biological signaling or function can also be important. The latter could include micro- or macronutrients like zinc or protein or an improved formulation of oral rehydration solution (ORS), supplemented with nutrients to help children with recurring diarrhea and early growth stunting. In all of these examples, we are using laboratory models to better understand and assess optimal interventions to complement improved access to safe water and sanitation to optimize the healthy growth and development of impoverished children worldwide.

Learn more about diarrheal disease and environmental enteric dysfunction (EED) in DefeatDD’s infographic.