In Cambodia, rising flood waters bring rise in diarrheal disease

|

In September, on site to train village health support groups on childhood diarrhea and pneumonia, the PATH team in Cambodia met with Chea Yeksim. Ms. Yeksim isvice chief and a village health volunteer in Duan Tom village of Baray operational district in Kampong Thom province. She spoke with us about the severity of childhood illness in her village and the gap in knowledge among families on how to prevent and treat diarrhea and pneumonia. In October, our team visited other villages, including a follow-up trip to Ms. Yeksim's village, and began thinking about the role of environmental factors in contributing to the number of high childhood deaths in the country.

In Chung Prolay village in Battambang province, a child defecates next to several sacks of rice; leaving behind a large mound of yellow, wet feces, where several other children are playing nearby. His mother picks up the feces with a handful of long, dry grass and disposes it in the field nearby. She then picks up a piece of discarded cardboard in a pile of rubbish on the ground, and wipes down the spot where the feces left a circular wet mark on the cement. Despite this incident, the children play in the area where the child defecated. A young boy not wearing underwear or pants sits on top of the spot for a brief rest. After he gets up, another child without pants on squats on top of the spot, his bare hands and feet placed firmly on top of the damp circle beneath him where the feces had lain.

In Ou Rumcheck village in Pursat province, cows walk through the villages defecating where they stand, and  chickens roam in and out of families' homes releasing their dung in yards where children play with rusting tin cans or eat fruit. It is common to see boys under the age of five not wearing any pants or underwear and even more common to see many children in the villages of Cambodia not wearing any shoes, exposing them to bacteria and germs that will get them very sick.

chickens roam in and out of families' homes releasing their dung in yards where children play with rusting tin cans or eat fruit. It is common to see boys under the age of five not wearing any pants or underwear and even more common to see many children in the villages of Cambodia not wearing any shoes, exposing them to bacteria and germs that will get them very sick.

Heavy rains over the past several weeks have affected health centers in Ms. Yeksim's village of Duan Tom in Kampong Thom province and in other rural parts of the country. It has been difficult for many Cambodians to receive aid or assistance, as it is also the worst flooding that the country has experienced in over a decade. Walking around Duan Tom, Ms. Yeksim tells us that most of the women in the village had attended her first mothers' class on diarrhea and pneumonia prevention, how she had made some hospital referrals for a couple of cases, and how some of women had been inquiring when the next training would be. But as we weave in and out of the homes in the village, trying to avoid slipping in the mud and stepping into piles of cow dung, I think about the other villages that are flooded, the families that might not be able to get to a health center in time to save the lives of their sick children, and the villages who may not have a volunteer like Ms. Yeksim who can teach ways to prevent and treat diarrhea and pneumonia.

I also think about a mother we met earlier that day at Taing Kok Health Center. She traveled from her village to the health center to get medicine for her child who had gotten sick with diarrhea, but because of the flooding her in her village, she was unable to bring him safely to the health center. How many other children might be suffering from diarrhea and pneumonia because of the recent flooding and how many families had to use the flood water for cooking, drinking, and also as a latrine because there was no clean water available?

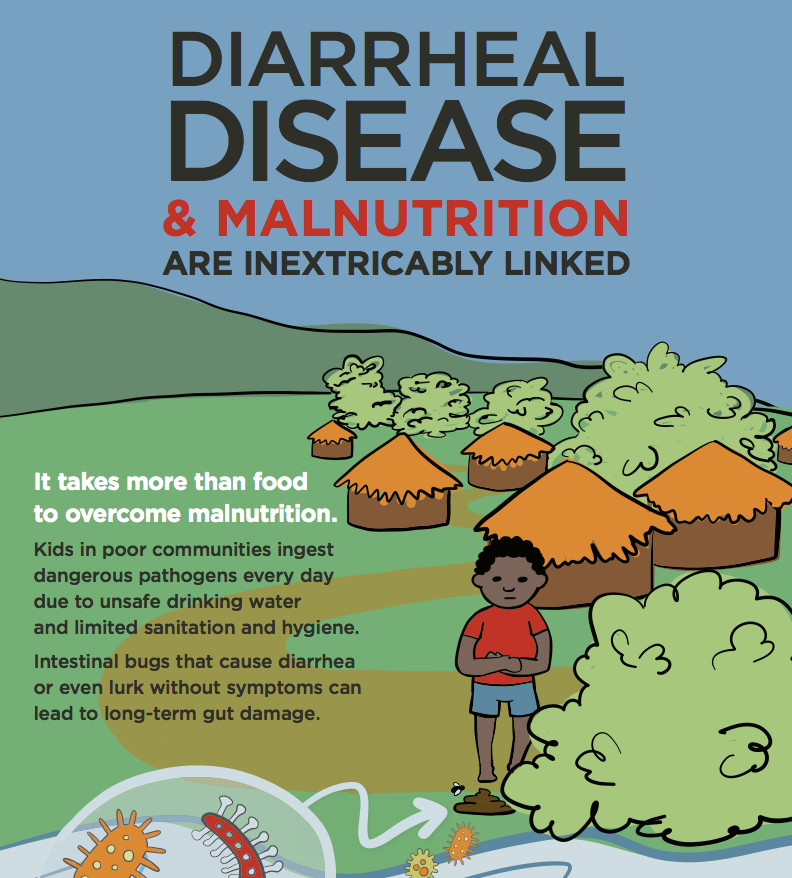

It then struck me that there are multiple factors contributing to the high number of children getting sick from  diarrhea and pneumonia in rural Cambodia. While there is an obvious need for the mothers' classes (especially with mothers asking when the next session would be), and the increase in the number of families that were seeking care from oral rehydration corners our project had established at clinics, many factors remain out of mothers' control, such as heavy seasonal rains that left behind high levels of still water carrying dung, garbage, and illness-causing bacteria. This water entered into their homes, ruined their rice fields, and made their children sick. There were also other uncontrollable factors such as the inability of families to purchase soap, shoes, and pants for their children because they simply cannot afford it.

diarrhea and pneumonia in rural Cambodia. While there is an obvious need for the mothers' classes (especially with mothers asking when the next session would be), and the increase in the number of families that were seeking care from oral rehydration corners our project had established at clinics, many factors remain out of mothers' control, such as heavy seasonal rains that left behind high levels of still water carrying dung, garbage, and illness-causing bacteria. This water entered into their homes, ruined their rice fields, and made their children sick. There were also other uncontrollable factors such as the inability of families to purchase soap, shoes, and pants for their children because they simply cannot afford it.

With everyday living conditions contributing to the high rates of diarrhea and pneumonia cases among children under five, how can we modify the environment so that we can mitigate the exposures and risks of the two illnesses that claim the lives of thousands of children around the world every day? How can we connect health policies and behavior changes to work with the environmental context to prevent children getting sick?

Next month we will bring you another blog post that explores these questions with a public health professional in Cambodia working on an integrated approach for preventing and treating diarrheal disease and pneumonia to gain perspective on what needs to be done to save the lives that are lost every day in the country.

-- Gizelle V. Gopez, Program Associate, PATH's Cambodia Country Program

This blog is part of a series. To read more, visit:

-- It takes a village... and its volunteers

For more information:

-- Healthy ecosystems, healthy people. What's the connection? A guest blog from The Nature Conservancy explains.

-- "The blue that blankets our home is its defining feature from billions of miles away and, often, the defining feature of our daily lives -Earth Day and every day." Learn about PATH's efforts to preserve our precious pale blue dot.

Photo credits: Gizelle Gopez