Building climate change resilience to water-linked diseases

As the lead of UNICEF’s Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) programs in Vanuatu, an island nation in the Pacific, Emily Rand feels she has a front row seat to climate change’s impacts on disease. Vanuatu is currently experiencing a dengue fever outbreak, and has recently experienced multiple category 5 cyclones and difficult droughts. Emily was therefore excited to moderate a session at World Water Week 2021 on building climate resilience with integrated solutions for WASH-related disease control.

Co-hosted by the Coalition against Typhoid and DefeatDD, the session featured four speakers who shared their research and experiences on how climate change will affect diseases – and how we as both WASH and public health professionals can improve our programming to adapt to climate change.

Dr. Daniele Lantagne: Links between diarrhea and climate change

To help us set the scene for our discussion, Dr. Daniele Lantagne from Tufts University shared an overview of the real-world impacts of climate change on enteric disease. She shared that diarrhea, which is the third largest cause of death in children under five, increases with temperature and is related and correlated with both precipitation and weather. Based on data, climate change will increase diarrhea in general—on average, we’ll see a 7% increase in diarrhea cases per degree Celsius temperature increase.

Dr. Lantagne explained that the changes in water-linked diseases will be driven by climate’s impacts on both hydrology (the study of the distribution of Earth’s water) and pathogen microbiology. At the community level, hydrology changes the water that is available, and pathogen microbiology changes water quality. We will see new waterborne pathogens in areas that did not previously know the disease. And, as Dr. Lantagne noted, we should be prepared.

Dr. Antar Jutla: Modeling impacts of climate change on cholera

Next, to give us more data to really understand this topic, Dr. Antar Jutla, from the University of Florida shared his work on modelling the impact climate change will have on the burden of enteric diseases, specifically on cholera. He noted that the ability to predict disease outbreaks is critical if we want to understand how climate will affect diseases and to be able to define intervention points for reducing impacts on human health.

A video illustrated his team’s prediction of the burden of cholera in Africa throughout the next century. By the 2060s, his modeling predicts that the highest burden of cholera will be in central Africa due to drought and heat. Another video showed a map predicting cholera in Sudan projected on top of a Google images map of the country, which allowed users to zoom in and see which specific populations in Sudan would be most impacted. As Dr. Jutla noted, this would allow public health and WASH professionals to target interventions for the most vulnerable populations.

Finally, Dr. Jutla emphasized the need for many different types of data and considerations to inform modeling work on climate and health. His modeling takes into account global climate change and variability, geophysical processes, water-ecological processes, pathogen survival and growth factors, sociological determinants of health, and civil infrastructure. As you can imagine, bringing these types of data together requires working across several disciplines.

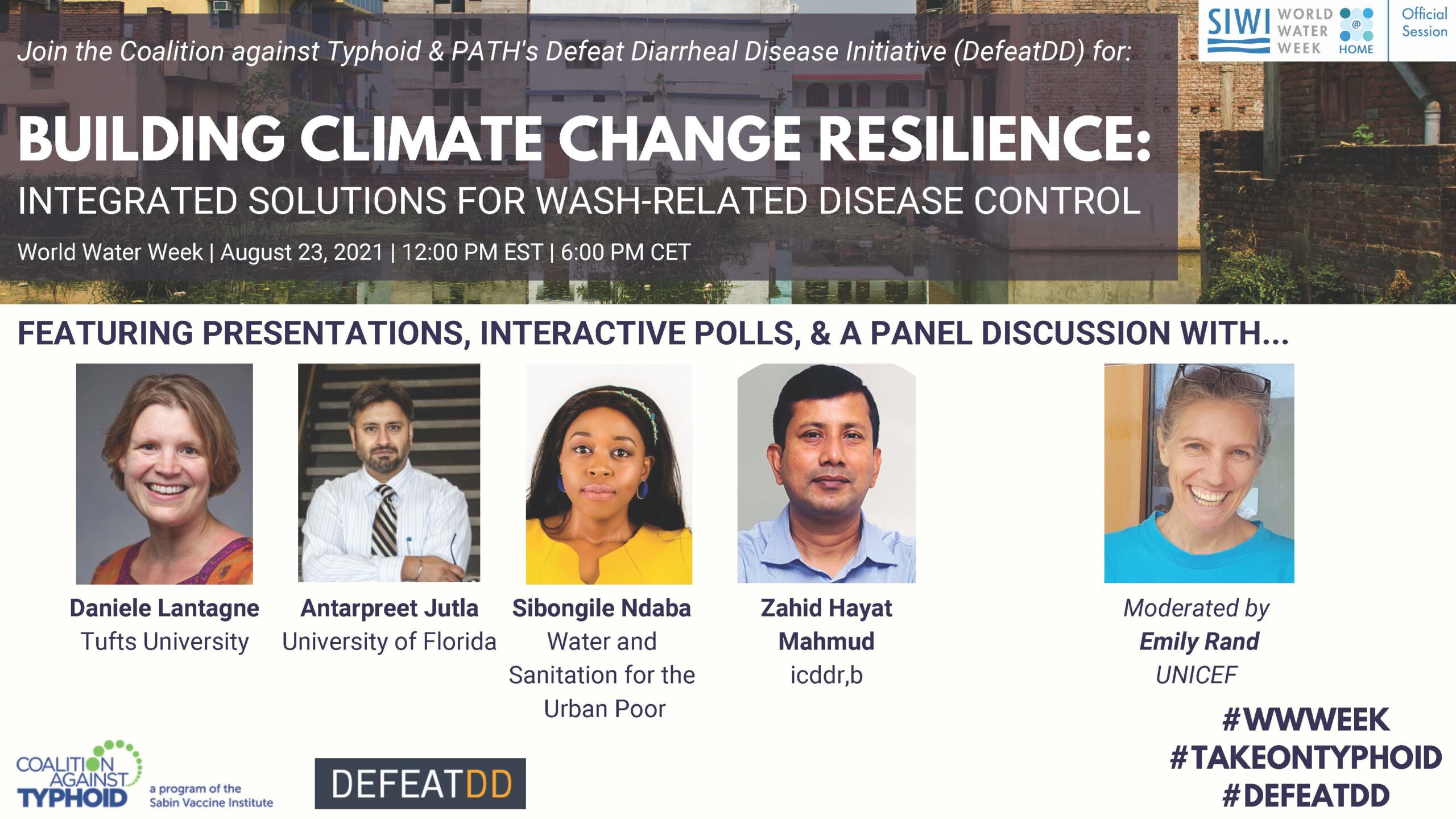

Participants answered poll questions during the session. Cholera was the most popular response to this question.Dr. Zahid Hayat Mahmud: Lessons from the Rohingya refugee camps

Participants answered poll questions during the session. Cholera was the most popular response to this question.Dr. Zahid Hayat Mahmud: Lessons from the Rohingya refugee camps

After gaining an understanding of the problem and how to track it, we heard about potential solutions. Dr. Zahid Hayat Mahmud from the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) shared work his team has done to conduct disease surveillance to identify sources of water contamination—and thereby inform WASH interventions—in Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Given that climate change is expected to increase migration, displacement, and urbanization, and Bangladesh has already been heavily impacted by climate change, this experience has many implications for global climate change adaptation.

During the panel session, Dr. Mahmud shared that 10% of water sources and 35% of household point-of-use water samples collected by his team in the refugee camp were contaminated with E. coli. Much of this was linked to groundwater. Therefore, icddr,b recommended to authorities to not use groundwater for the camp’s drinking water but instead look for natural sources like streams, rainwater harvesting, or treated surface water. Dr. Mahmud’s team also found that improving the efficiency of fecal sludge treatment plants in these settings can make a big difference. Finally, given the difficulty of controlling contagious and waterborne diseases in densely populated settings like refugee camps, Dr. Mahmud stressed the need to rely heavily on vaccination alongside water and sanitation improvements.

Sibongile Ndaba: Lessons from tackling cholera through WASH in Zambia

Finally, we were joined by Sibongile Ndaba from Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor (WSUP), who oversees the business component of all water supply and sanitation interventions in Zambia. Sibo described how WSUP is working on WASH interventions to help mitigate water scarcity and prevent cholera outbreaks in Zambia. In Kanyama, Lusaka, WSUP implemented a fecal sludge management project that introduced safe emptying and disposal of fecal waste from pit latrines that contribute to ground water contamination. This project was targeted to Kanyama because WSUP found that pit latrines were a source of cholera outbreaks in the area. Sibo also emphasized the importance of sustainable policy change through Lusaka’s adoption of a city-wide fecal sludge management plan.

Reaching across the aisle to connect WASH and public health

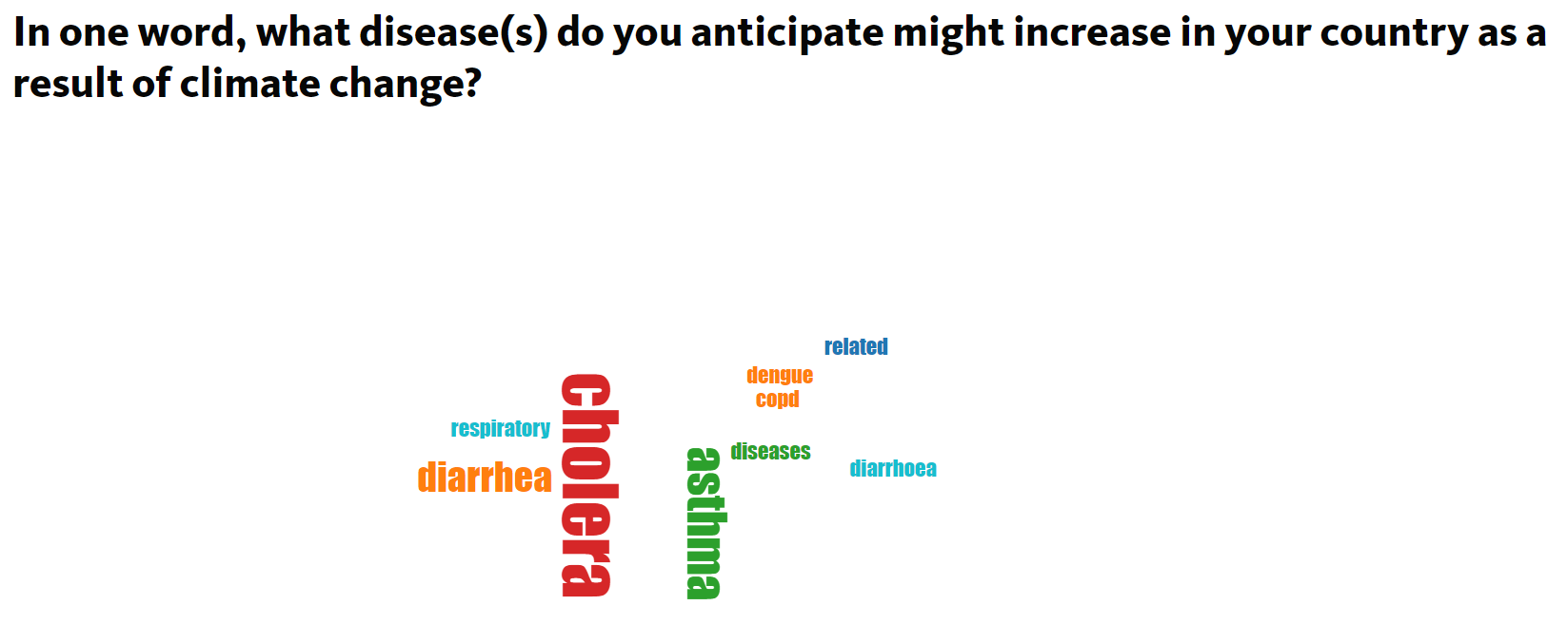

The session was created after practitioners working on enteric diseases realized there wasn’t enough dialogue between WASH and others in the public health community on integrated solutions for WASH-related disease control. From that perspective, the session was a huge success – as it brought together experts and participants from both public health and water and sanitation.

This session poll found that the participants came from a mix of both public health and WASH backgrounds.Improving WASH programming to better inform disease prevention—which is an urgent consideration in the face of climate change—will require cross-sectoral coordination. As Dr. Jutla said in his closing remarks, “Reach across the aisle. Learn the language the other discipline speaks. That’s how communication will start.”

This session poll found that the participants came from a mix of both public health and WASH backgrounds.Improving WASH programming to better inform disease prevention—which is an urgent consideration in the face of climate change—will require cross-sectoral coordination. As Dr. Jutla said in his closing remarks, “Reach across the aisle. Learn the language the other discipline speaks. That’s how communication will start.”