15 years with DefeatDD

Silly faces are the universal language of childhood. Here, I’m tapping into it in Patna, Bihar Province, India. Photo: PATH.

When you spend as long as I have in one organization, life-stage metaphors become part of one’s regular job description. I often say I grew up at PATH. And since I was a Program Assistant on the team that launched DefeatDD, the initiative feels like a child raised by our little village—now a teenager at 15 years old!

Looking over past campaigns is like paging through old family photo albums. My personal and professional development are inextricably linked. How can I disentangle them? Tara, DefeatDD Communications Associate, reminded me that I don’t have to. That’s what the blog is for!

Here are four ways DefeatDD has shaped my perspective as a communicator, an advocate, and a colleague.

Finding courage

I lean toward risk-aversion by nature, so it is easy for me to imagine myself in a parallel universe starting my professional career in a position where those qualities are reinforced and ultimately self-limiting.

You can’t exactly hesitate and hand-wring if you are going to talk about poop, though—at least not if you want to get people’s attention. A bit of risk-taking was built into the job description from the start. It takes courage to implement creative and unorthodox ideas, and it was modeled for me at a critical moment in my personal and professional development, helping me pivot toward a more open posture than I might otherwise have embodied if I’d been pushed in a different direction.

Were Eileen Quinn, Elayna Oberman, and I supporting Red Nose Day, or was it casual Friday? I’m not telling. Photo: PATH.

Eileen, DefeatDD’s director, provided an anchor of safety from which our team could exercise the courage that creativity demands, giving us permission to experiment and learn along the way. This mindset imbued the project with a vitality that set it apart, and it became a positive, reinforcing cycle.

Elevating an issue, not an organization

Starstruck! In New Delhi, India, Erika Amaya and I got to meet Chamki (left) and Googly (right), at the Sesame Street office. They joyfully and enthusiastically shared with us how they teach children about handwashing and other important health lessons. Photo: PATH.

Former US President Harry Truman said, “It is amazing what you can accomplish when you don’t care who gets credit.” I think of this quote often when I think of DefeatDD, where our job was to elevate the issue of diarrheal disease rather than the work of any one organization. And we forged conversations among actors who otherwise would never have appeared in the same rooms, like vaccination and sanitation stakeholders.

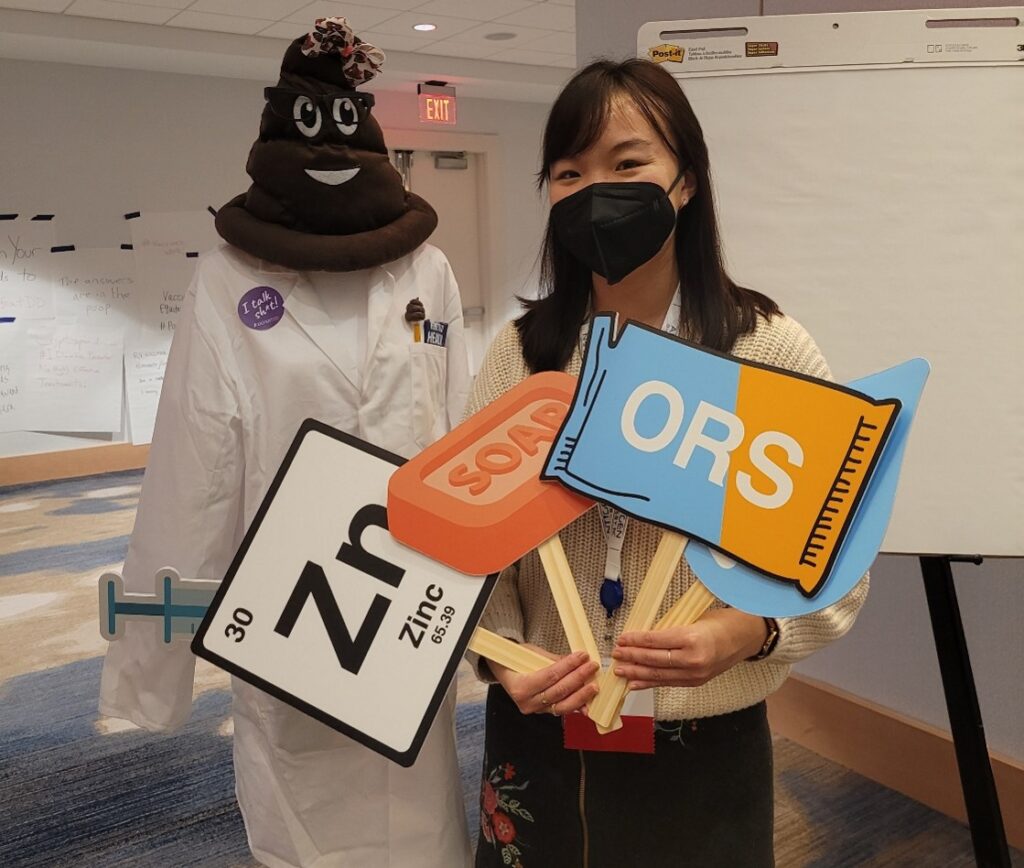

Poo Guru looks on in approval as PATH colleague Emily Hsu demonstrates an integrated approach at the 2022 Vaccines against Enteric Diseases Conference. Photo: PATH.

There’s nothing like a toilet stall photo backdrop to break the poo taboo. Left to right: Fred Cassels, Eileen Quinn, Laura Kallen, Nicole Bauers, Allison Clifford. Photo: PATH.

Some project mandates are inherently more targeted, but the many years of seeking collaborations with unexpected or unlikely stakeholders have developed in me an instinctive reflex to scan for such opportunities even when it’s not explicitly in the job description. I can’t think of an instance where this mindset does not add value; novel combinations are fertile ground for innovative breakthroughs.

When it got personal

The opportunity to tell stories about families and health workers has been an immense privilege. These are the people who deserve all the recognition, and I’m proud that DefeatDD could be a platform for them.

It is impossible for me to write a reflection on how DefeatDD impacted me without mentioning Alfred Ochola, affectionately known as Dr. Diarrhea. This one-man powerhouse did it all, whether or not it was in his official job description. He single-handedly brought oral rehydration corners—designated areas in health facilities for providing oral rehydration therapy— back to life in numerous clinics in rural Western Kenya. Along the way, he would surreptitiously examine a patient, elicit smiles from worried mothers, or troubleshoot issues with a community’s water source. And you never knew when he would break into dance.

Neither hill nor stream could stand in the way of Alfred’s community visits. Photo: PATH/Tony Karumba.

In 2021, Alfred passed away from COVID-related complications. I remember exactly where I was when I heard the news, and I remember the timing, because it was a few weeks after I’d received my first COVID vaccine. Vaccine shipments had arrived in Kenya just weeks or maybe even days too late for Alfred to access them. He needed the shot more than I did, yet I was protected and he wasn’t. I’d been writing about the urgency of vaccine access for more than a decade, but that was a moment I felt in my bones the sadness of a solution that came too late.

Since I met him, “What would Alfred do?” became a mantra that helps center me on the right priorities in child health. I can’t say I always follow where that question leads: he shyly evaded praise while I regularly sought to put him in the spotlight, for example. He was always looking toward the children of the communities he served, singularly focused on how to best help them. But I think telling Alfred’s story is a boon for those children, too, if it inspires others to follow his example.

Healthy children are the foundation of fruitful societies

When I first started learning about the causes of child mortality in low- and middle-income countries—how children were dying from commonplace infections like pneumonia and diarrhea—I was indignant about the unfairness of it. As I’ve learned about the critical development that happens in the first five years, and especially in the first 1000 days of life, I’m even more passionate about investing in child health and well-being. When we miss that window of opportunity, the consequences of diminished potential cast lifelong shadows: in lower IQs, higher risks of chronic illness, diminished income-earning capacity. Child survival shouldn’t be the end goal; the goal should be a strong start that sets children up for lifelong success, ultimately resulting in a more productive population.

Meeting Teresa and baby Vusi in Lusaka, Zambia, was a highlight of my DefeatDD experience. Vusi had just received his rotavirus vaccine. Photo: PATH/Gareth Bentley.

My work on DefeatDD has felt poetically fitting because I don’t have children of my own. Not all of us will birth children, but we all have a role to play in caring for them, and this is one way in which I have done so. In that regard, I will continue to be an aunt (both biological and honorary) and a strong advocate for children everywhere. I hope all DefeatDD advocates will continue to do the same.

As Alfred would say, “Hello? Are we together?”

Together, we can still DefeatDD. Onward and upward.