The Question We Should be Asking about Measles Vaccinations

|

On 13 February 2014 in Guinea, a woman holds her son in a sling on her back as he is vaccinated against measles in Conakry, the capital. The immunization was administered as part of a massive emergency vaccination campaign against the disease. The government-led campaign, which aimed to reach over 1.7 million children across the country, in response to an increase in the number of measles deaths and suspected cases of the disease.” Photo credit: UNICEF/NYHQ2014-1923/La Rose.

Measles, a disease that has been all but forgotten by many families in high-income countries, returned as front-page news in America, Canada, and Germany this year. I've seen these articles appear on my news feeds on Twitter and Facebook and watched as debates emerged about what role the government has in requiring parents to vaccinate their children. This is an important public health discussion, but absent from these articles and online debates is the story that millions of families around the world are desperate to vaccinate their children against measles but can't because they lack access to this affordable and effective life-saving vaccine. Because: measles vaccines are life-saving.

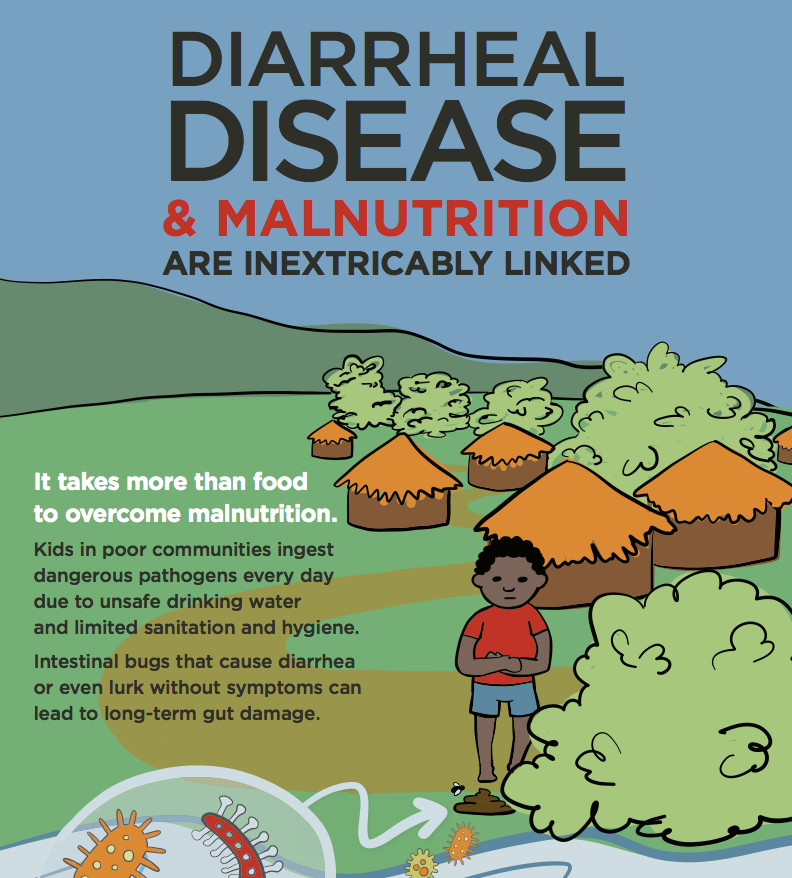

Measles is an infection that weakens the immune system, which can lead to other infections such as severe diarrhea, pneumonia, and encephalitis. In low-income countries, where children have limited or no access to medical treatment and are often malnourished, getting measles and then severe diarrhea or pneumonia can be deadly. Between 2 - 15 percent of children who get measles in low-income countries will die from measles-related deaths and in the worst outbreaks up to 25 percent of children can die. That's why so many families literally refer to measles vaccines as miracles - because they know the toll of not vaccinating.

When communities host measles vaccination campaigns, we see families travel by boat and walk great distances to ensure their children are vaccinated. Despite families demanding vaccines and their willingness to go to great lengths to protect their children against measles, global measles vaccination efforts are facing significant funding challenges. For example, a large-scale vaccination campaign in Ethiopia that aimed at vaccinating roughly 40 million children (9 months to 14 years old) was postponed until next year because of funding shortfalls. And still, there aren't enough funds to vaccinate over 28 million children in Ethiopia next year. While Ethiopian children wait for the global community to fund this vaccination effort, measles outbreaks rage in their country. As of mid-August, Ethiopia had 16,000 suspected cases of measles. In a country that is facing a drought and more than 28 percent of children are malnourished, these children cannot wait to be vaccinated.

This week, immunization experts from around the world are gathering in DC for the Measles & Rubella Initiative Annual Meeting. In presentations and side conversations, I've heard the frustration in the voices of doctors and public health experts who see firsthand parents who are eager to vaccinate their children, but can't because we lack the resources to reach every child. I find myself hearing questions about why parents aren't vaccinating their children in high-income countries and I wonder why we aren't also asking, “How can we let 40 million children not get vaccinated this year when we have an effective vaccine that costs just $1/child and their parents are desperate to protect them from measles?”