This child received a vaccine against rotavirus, this child did not

|

This post is part of the #ProtectingKids blog series. Read the whole series here.

Dhaka was people. Everywhere I looked: people. Crowded streets, makeshift markets, farmers, businessmen, families, and animals. More than 15 million people live in the 315 square milesthat comprise the Greater Dhaka area, capital of Bangladesh. With so many in such close quarters, imagine if an outbreak hit.

An outbreak hit.

When I visited in 2009, Dhaka was in the grips of a terrible diarrheal disease outbreak: not only cholera striking all ages, but also rotavirus stalking the city's children. For weeks, the hospital of the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) admitted upwards of 600 inpatients daily Since the hospital had just 350 standard beds, massive tents handled patient overflow just outside its front steps.

We arrived in Bangladesh to witness a pivotal moment that demonstrated just how important a vaccine against rotavirus could be. Dhaka was our first stop, but soon we travelled farther in-country to learn more.

Our driver snaked through the city streets, and pavement turned to a short dirt path. Suddenly—the city at our backs—lush greenery and a calm waterway lay before us. Crowds again gathered, this time to help shove off as our speedboats started down the Dhonagoda River. The destination: Matlab Health Research Centre, to document PATH's clinical trial on rotavirus vaccine effectiveness.

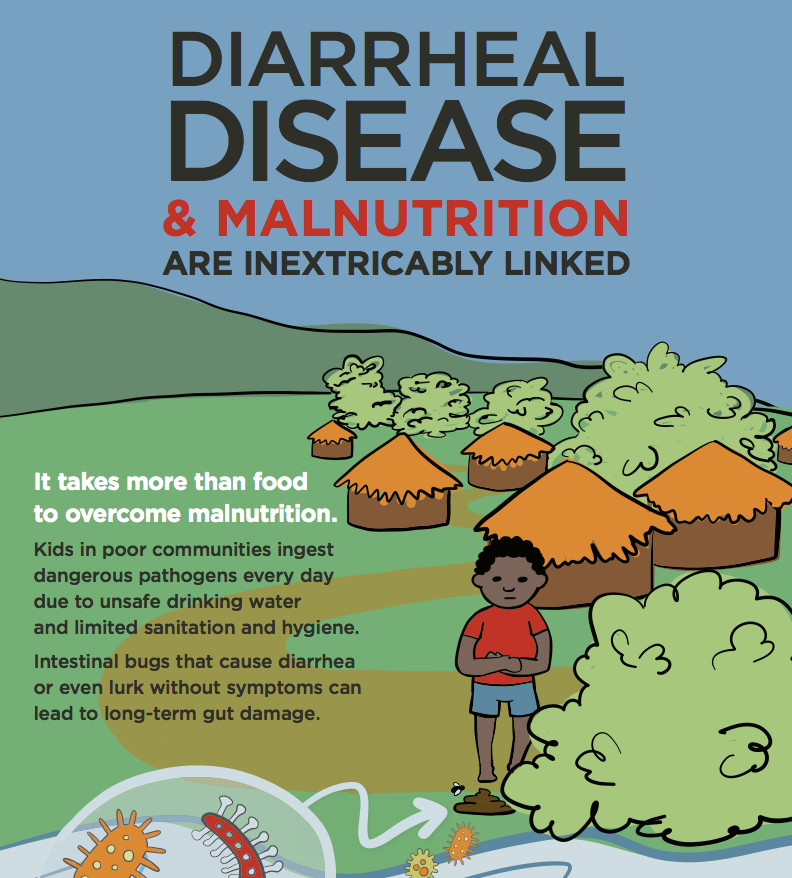

Though we found ourselves far removed from Dhaka's outbreak, diarrheal disease and rotavirus still threatened. At ICDDR,B's Matlab Hospital, I ment Samsunahar and her daughter Rehana. Rehana was 6 months old when she fell ill, suffering persistent diarrhea and vomiting at home for two days. The local doctor advised saline, but Rehana's condition did not improve. Samsunahar traveled three hours by auto rickshaw to the Matlab Hospital. When we met her, Rehana's health was finally improving, but she had her own long journey ahead. Her attending doctor was fairly sure she had rotavirus, but due to the volume of cases, not every diagnosis can be confirmed in the laboratory. After a treatment protocol of zinc, breastmilk, and ORS, Rehana and Samsunar could return home.

Though we found ourselves far removed from Dhaka's outbreak, diarrheal disease and rotavirus still threatened. At ICDDR,B's Matlab Hospital, I ment Samsunahar and her daughter Rehana. Rehana was 6 months old when she fell ill, suffering persistent diarrhea and vomiting at home for two days. The local doctor advised saline, but Rehana's condition did not improve. Samsunahar traveled three hours by auto rickshaw to the Matlab Hospital. When we met her, Rehana's health was finally improving, but she had her own long journey ahead. Her attending doctor was fairly sure she had rotavirus, but due to the volume of cases, not every diagnosis can be confirmed in the laboratory. After a treatment protocol of zinc, breastmilk, and ORS, Rehana and Samsunar could return home.

Further afield, in Kaladi village near Matlab, I met Shobarani, her 2-month old daughter Priti, and Priti's proud big brother, 10-year-old, Shawon. A shy but cheerful and healthy boy when I met him, Shawon was very sick with rotavirus as a baby, Shobarani told me. Like Rehana, he spent several days in the hospital for treatment and recovery. The memory of fear for her son's life never left Shobarani. When she learned about a clinical trial for a new vaccine against rotavirus at her local clinic, Shobarani promptly enrolled her newborn daughter Priti. As she asserted to me, “It is very important to protect this child.” With a promising vaccine available through the clinical trial, she was able to keep her daughter safe in a profound way that she couldn't offer Shawon a decade before.

Further afield, in Kaladi village near Matlab, I met Shobarani, her 2-month old daughter Priti, and Priti's proud big brother, 10-year-old, Shawon. A shy but cheerful and healthy boy when I met him, Shawon was very sick with rotavirus as a baby, Shobarani told me. Like Rehana, he spent several days in the hospital for treatment and recovery. The memory of fear for her son's life never left Shobarani. When she learned about a clinical trial for a new vaccine against rotavirus at her local clinic, Shobarani promptly enrolled her newborn daughter Priti. As she asserted to me, “It is very important to protect this child.” With a promising vaccine available through the clinical trial, she was able to keep her daughter safe in a profound way that she couldn't offer Shawon a decade before.

Remembering these moms reminds me that, when we look inside the crowds, across the river, even into verdant fields and rural villages—people are much the same. We all want to protect our children, and we all value our health: Samsunahar, Shobarani, even me, and you too. At this fundamental level, superficial differences fade away.

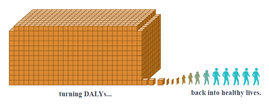

Our opportunities for healthy lives, however, can be drastically varied. But they shouldn't be. In the case of immunization, worldwide we know that vaccines work, they protect kids from Birmingham to Bangladesh, in cities and villages, and all points in between. Every parent should have the chance to offer such protection, and every child should have the chance to realize vaccines' lifesaving potential.

Photo credits: PATH.