Catching up with ColaLife

|

Two years after we first met ColaLife in Lusaka, Zambia, we welcomed them to Seattle. The city didn't disappoint: ColaLife founder Simon Berry lamented a forgotten raincoat upon his introduction to typical Northwest weather; and he even garnered his own stern warning from a local police officer after jaywalking. (We do not jaywalk in Seattle.)

Simon and DefeatDD chatted over coffee, Seattle's own beverage of choice, catching up on ColaLife's accolades and lessons of the past two years.

ColaLife has grown quite beyond its original concept of transporting anti-diarrhea kits in the empty space of Coca-Cola crates, hasn't it?

Yes, through our trial, we learned that the most important thing is not the space in the crates, it's the space in the market. But the original concept has a lovely logic: Coca-Cola gets everywhere, medicines don't; put the medicine in the crate, and it gets there too. But when we really drilled into it, we learned that actually it's incredibly naive. The ratio of demand for bottles of Coca-Cola would never match the ratio of the kits filling up all that space. That would be 10 kits for every 24 bottles of cola!

It was quite difficult to walk away from that original idea, but we had to. Because that concept, the crate-centered design, really captured people's imaginations. The awards we've won based on that are incredible, and they're even beyond the health sector - product design of the year, packaging design of the year. But the trial is actually telling us that fitting in the crates is not what's most important, in terms of getting the kits in people's homes.

However, the doors might not have opened without that original concept, so it was ultimately important. And we learned so much about distribution and working with shop owners. And in some certain circumstances, in the future, the crate design might work. Imagine a humanitarian crisis: a cholera outbreak isn't going to stop Coca-Cola trucks. Just for a month you could put the kits in the crates, flood the market. So it could have a role, but it's not the sustainable approach.

In addition to a change in the kit's design, what would you say are the one or two key lessons you've drawn from the trial?

When we initially engaged partners, we focused on public/private partnerships at the global level. But as we've implemented the distribution and sales, we found that grassroots public/private partnerships were most important: the partnership between the retailers in the community and the government-run health centers. We couldn't do this without the Ministry of Health at our side.

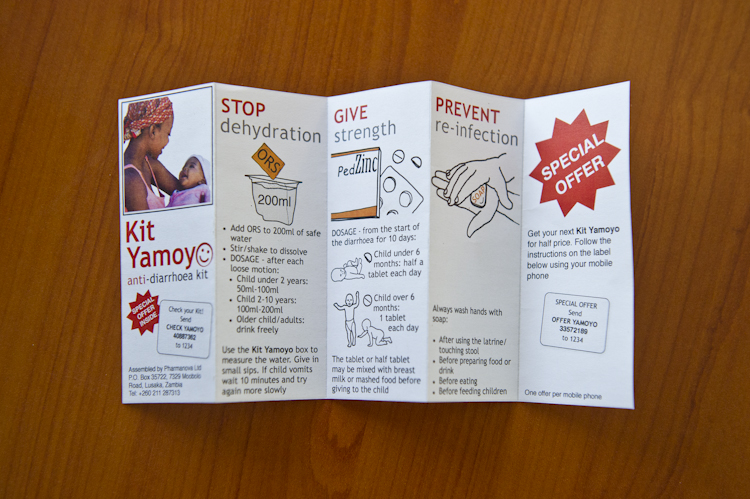

On our latest trip, we went to a district I'd never been to before. There were 150 meters between the health center and the shop. Underneath the tree, outside the shop was a woman with a very sick child. She had two ORS sachets from the clinic and 4 tablets in a clear plastic bag. And in her other hand, she had a Kit Yamoyo. The clinic had said, “Here is the medicine, but also go and get a Kit Yamoyo from the shop.” That was a public/private partnership at work.

Another lesson is about respecting local systems. If you are going to intervene, do it in a way that strengthens local systems rather than undermines them. Don't make yourself indispensable. As a foreign body, quite literally, we should be a transient presence. It's no good if the whole thing depends on ColaLife because when ColaLife leaves, the whole thing is going to collapse. But because we're not part of the local system, we can leave. The product is in the market, it's being produced locally. Any wholesaler or distributor can ring up our local manufacturer and order the kits.

What have been the biggest highlights in being involved with this project and seeing it grow?

Every week, something amazing happens. Little kids drinking ORS or wanting to drink ORS from our kit - that is the highlight. Mothers love it. We inquired deeply into what they thought of the kit, whether they would buy another one, etc. And we didn't get a single negative response. From mid-line (6 months into the trial) to end-line, we asked people if they thought the kit was affordable. At mid-line, it was a respectable amount; by end-line, that had doubled. People would buy it again and they thought it was valuable.

In October, we'd just started the trial and went out to one of the districts. We spoke to a woman whose child had diarrhea, since April, she said. The clinic had given her ORS each visit, and she gave it to the child, but the child never fully got better. And then she had gotten the kit, with zinc. And there the child was—running around, being naughty, doing everything a small child should do.